Defining design systems seems a daunting challenge. It’s not as if our community hasn’t made many, many, many, many, many, many, many, many, many, many, many, many, many attempts. Recently, Sarah Federman wrote about distilling it into its essence and warns us to avoid getting trapped defining things and being dogmatic about what it is and isn’t.

Design systems is a growing field formed by vibrant, collaborative voices. It is important to posit what a system is and how it fits, or we risk undermining its value due to incoherent understanding. We shouldn’t suffer challenges, and there’s common ground to gain. My livelihood depends on it, selling ~15–25 design systems engagements a year to clients understanding the outcomes and outputs (hint: not just UI kits, code, and doc) and why they matter.

If I have ~30 seconds in an elevator or over animated slides, I’ll lead with:

If only 10 seconds, I’ll say:

Formally, a system is a set of interconnected parts forming a unified whole. In the case of design systems, this definition actually alludes to not one but three interrelated systems you’ll need to solve for to be successful:

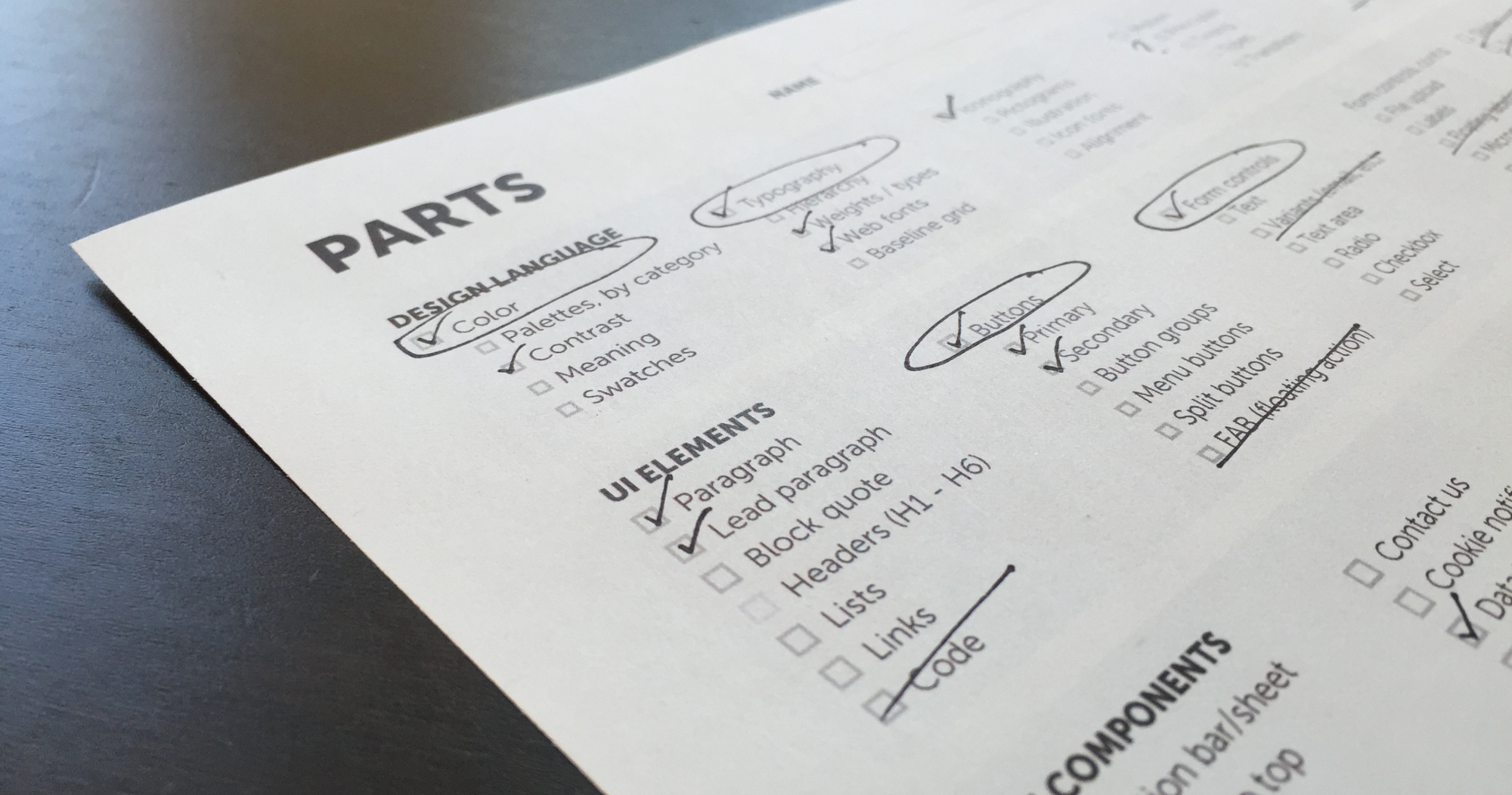

To its primary customers, the system is a set of tangible outputs that they encounter on a day-to-day basis. I’ll start plainly with:

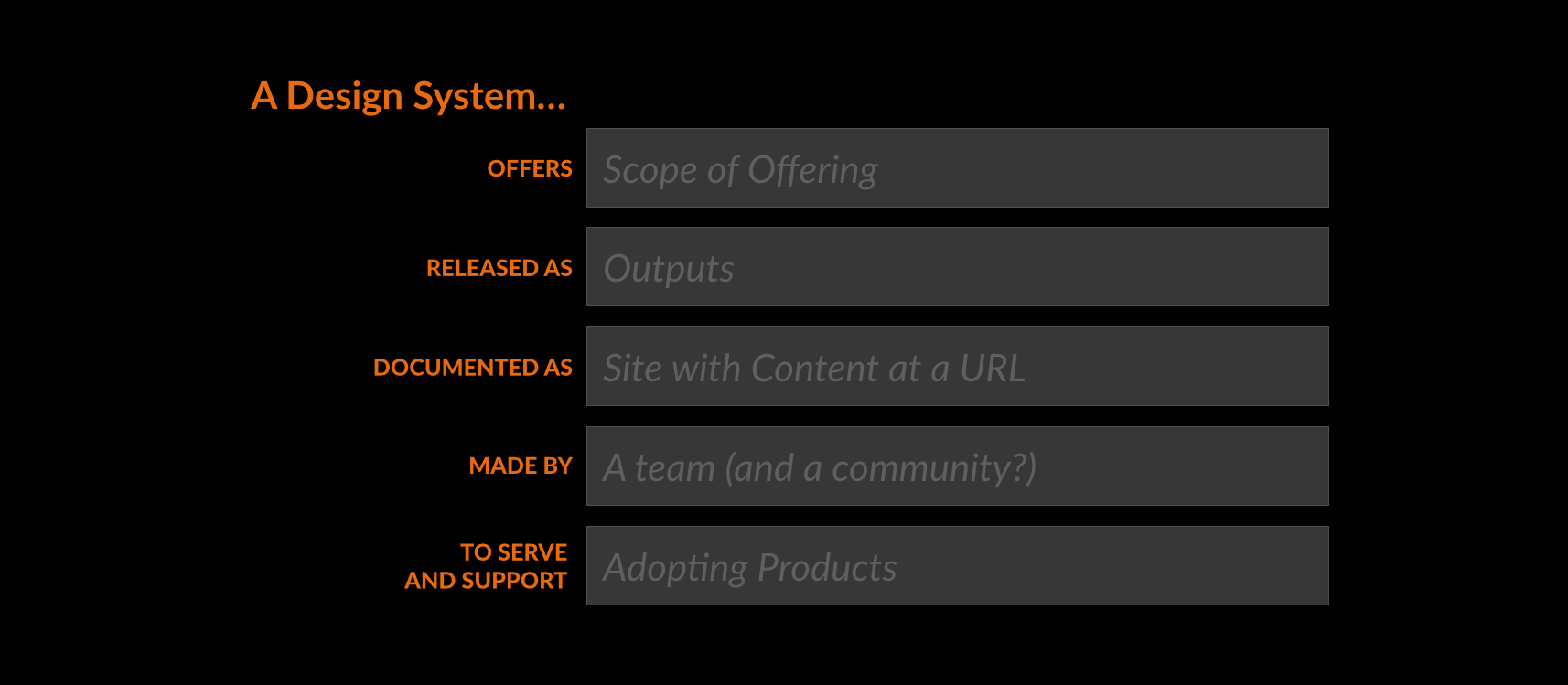

These days, a system of parts connects a codifed visual style (e.g., color, space, typography) to composible UI components (buttons, forms, headings, so much more) used to design and build interfaces.

This starting point packs a punch of intention, revealing beliefs: A system serves developers and designers, in that order. A system must be well-documented. A system must offer style and UI components. Yet every system is different, so I’ll expand a system’s scope to include:

This variability fosters useful conversations that draw boundaries around what an organization wants and needs. Some concerns (always style and components) are realized far more often than others (editorial guidance and data visualization).

Words like “offer” and “released” are intentional, casting the design system as a product satisfying the needs of customers (chiefly, developers and designers making products of their own) through tangible outputs they use.

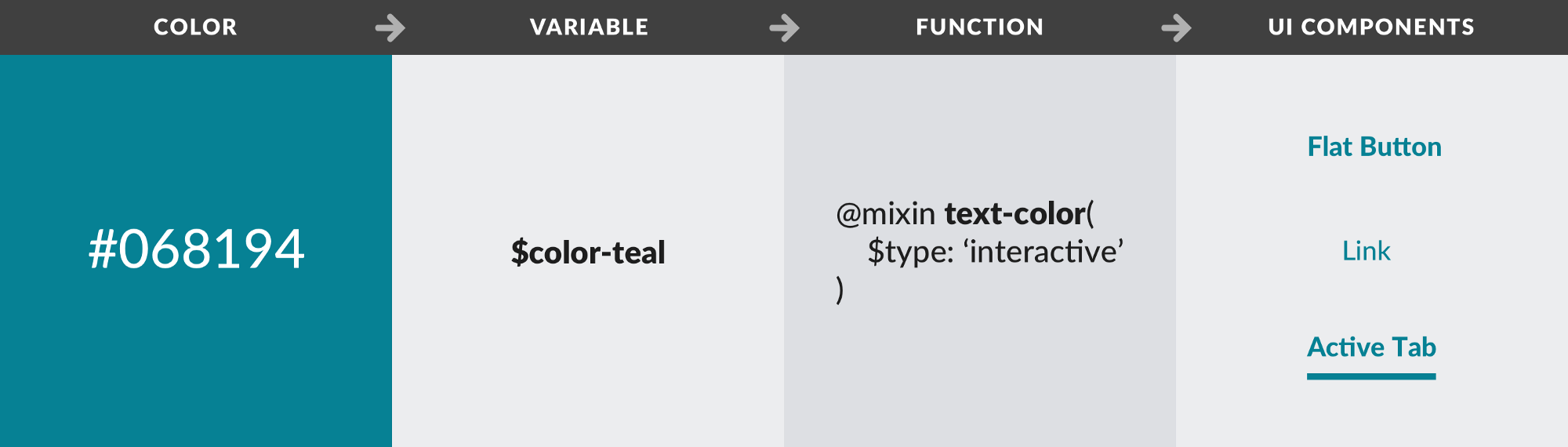

Invoking product concepts trigger a cascade of concepts useful for those familiar with product management applicable to a system too: roadmap, backlog, releases, program increments, sprints, dependencies. However, to focus only on development of parts risks missing what makes systems work. Especially, the system’s customers!

Design systems invest in marketing to product teams to consume the kit of parts to form a unified and cohesively holistic experience. Fostering adoption requires clear messaging to sell others to adopt system and improving themselves (individually and collectively) by realizing its benefits over time as a dependency.

Product management also evokes how design systems fit in product operations , such as DevOps delivery (“How do we release it? How is it automated?”), integration (“How do we version? What’s a breaking change? How, how frequently, and when do we upgrade?”), and infrastructure (“Where’s our repo? Where’s our doc hosted? Is it public?”).

Easy to miss in the definition above is supported for, framing the support and service of the customer. Effective documentation is essential. Beyond that, there must be paths to and time for providing help, responding to requests, patching defects, and consulting, all in an environment that’s open and responsive.

To cast a design system (and the effort needed to make it work well) as just developed style, components, and assets — to the exclusion of the marketing, service, integration and operations that success depends on— is too narrow.

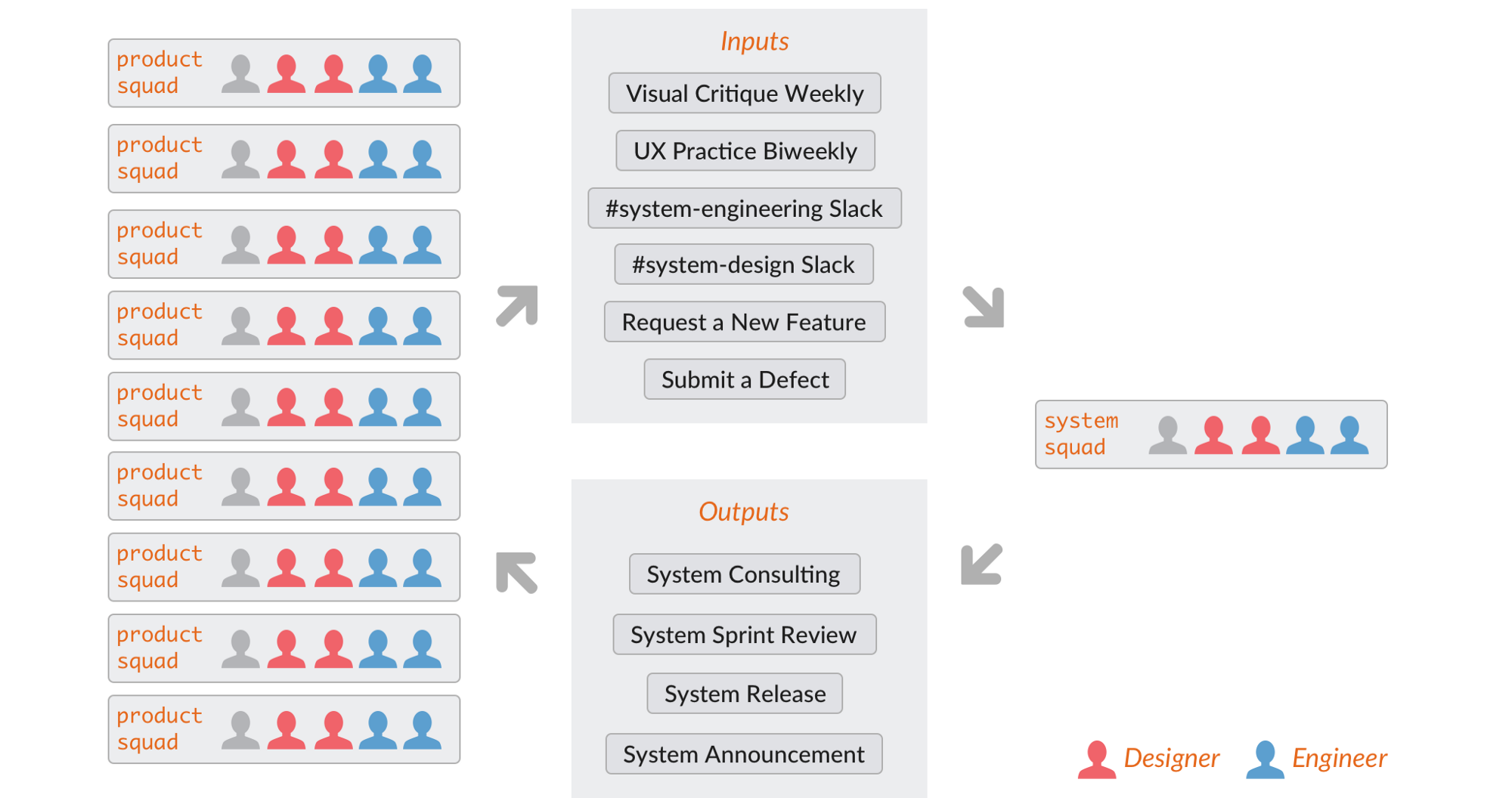

To help stakeholders understand the impacts of a system, I also route conversation through the people and activities required to operate a system.

Characterizing a system team as a product squad sets the choice in terms familiar to product and marketing professionals: is this important enough to put a team behind it? That team can adopt rituals, showcase work, and evolve a roadmap to become part of the fabric of how enterprises make products.

In cases I’ve observed, this team is responsible for the workflows, connections, and community engagement across an enterprise to decide how a system is applied and evolved. Historically referred to as “governance,” I’ll avoid that term to favor a tone of collaboration over control.

From the outside, a designer, engineer, or someone else in a community may not sense the level of execution behind such activities. That doesn’t mean that they aren’t developed, operated, supported, and used deliberately for months or years. This execution of community interactions is an effortful yet intangible product that make a system successful.

While not my intent, this writing returned me to the framework of a Parts, Products, and People workshop I’ve run for years. This activity steps participants through a prescribed protocol to detail what parts their system needs, what products it’ll apply to, and who does the work.

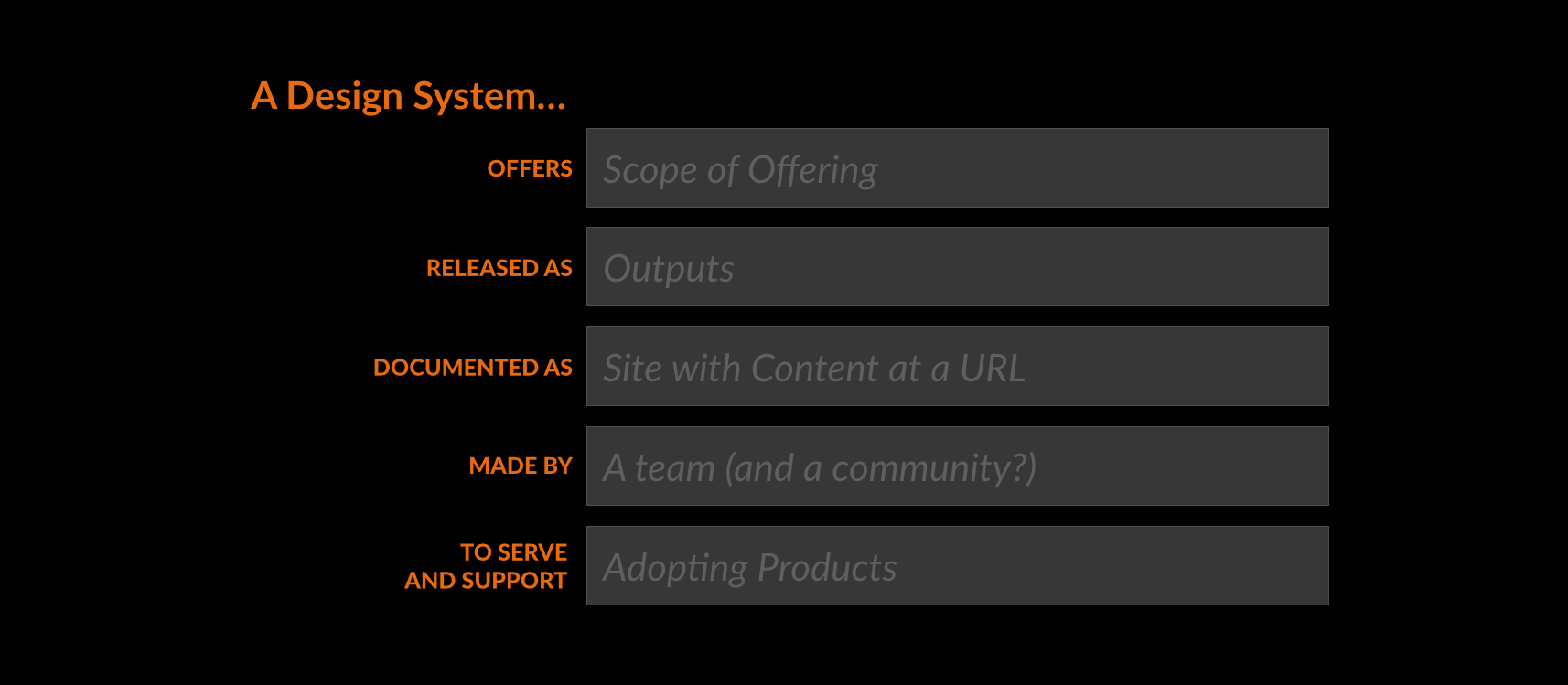

However, it’s reasonable to precede or replace this meticulous activity with a leaner, fill-in-the-blanks template to ground understanding:

Our design system offers ___[kit scope]___ released as ___[kit outputs]_ and documented at ___[kit doc site]_ produced by ___[people]_ in order to serve ___[products]___ products and experiences.

Over years of contributing to design systems, this statement would yield similar yet always unique answers. A system I’m working on now would fill these blanks as:

Our design system offers visual style, accessible UI components, charts, editorial guidance, UX patterns, and branding released as an HTML & CSS framework via npm, Sketch, and other PDF & AI templates and documented at designsystem.companyname.com produced by a systems team of 1 design director, 1 product manager, 2 designers, 3 engineers and a community of ~15 community contributors in order to serve ~50 web apps, a few native app and limited branding products and experiences.

A system I am starting now exhibits a different composition that necessitates a different approach to how it’s made & consumed:

Our design system offers visual style, UI components, and accessibility proceduresreleased as an React component library and Sketch assets via Lingo and documented at designsystems.companyname.com produced by a systems team of 1 systems lead, 1 product manager, 1 designer, and 2 front-end developers partnering with a React-based engineering team in order to serve ~10 web-based and 2 native appproducts and experiences.

What flummoxes our community is the variability of systems composition. The consistent objective — adopting products producing a cohesive experience more efficiently — is reached through many potential means by involving different kinds of groups with varying areas of focus.

There’s no de-facto formula, no winning methodology (but we’re getting better). Instead, system success requires adapting how you define it to conditions and constraints of the enterprise it serves.

EightShapes can energize your efforts to coach, workshop, assess or partner with you to design, code, document and manage a system.