In “Pattern patter.”, Ethan Marcotte writes yearningly for more design patterns in our practice. For now, many teams build libraries reusable components. However, these libraries usually lack thoughtful guidance to resolve myriad forces at play to compose interfaces effectively. Today’s libraries are (just) a kit of interface parts.

Ethan hints at the gap between reusable snippet and principled guidance. The call for more patterns, in my opinion, it misses a point. Those “pattern” snippets aren’t patterns at all. At least not in the formal sense. Those snippets are components. And conflating the two confuses and clouds our judgment on why in-house teams don’t pursue patterns much anymore.

Let’s trace pattern history to understand the difference.

In learning patterns, designers immediately encounter Christopher Alexander’s inspirational A Pattern Language (1977).

The book is required reading (or browsing, since it’s THICK) for any aspiring design librarian. The book lays out myriad patterns — Arcades, Sequence of Sitting Spaces, Six-Foot Balcony, and 253 others — as a language options to ground sound architectural designs and decision making.

Alexander’s catalog sets a content model for each pattern we emulate today:

You can trace Alexander’s influence into software engineering with Design Patterns:Elements of Reusable Object Oriented Software (1994) by Gamma, Helm, Johnson, and Vlissides.

Design Patterns quotes Alexander’s definition of a pattern:

<div class="escom-pull-quote escom-pull-quote--light">

<div class="escom-pull-quote__the-quote">

Each pattern describes a problem that occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, <strong>without ever doing it the same way twice</strong> (emphasis added).

</div>

<div class="escom-pull-quote__attribution">

Chrisopher Alexander

</div>

</div>

The book then differentiates patterns from the components of today’s “living style guides:”

<div class="escom-pull-quote escom-pull-quote--light">

<div class="escom-pull-quote__the-quote">

Design patterns are not about designs such as linked lists and hash tables that can be … reused as is. Nor are they complex, domain-specific designs for an entire application or subsystem. The design patterns in this book are descriptions … that are [then] customized to solve a general design problem in a particular context.

</div>

<div class="escom-pull-quote__attribution">

Christopher Alexander

</div>

</div>

Unlike patterns, components we use are already built for domain-specific reuse within a system. For example, a button is built for the web using HTML and CSS snippets to apply a visual language (like Material Design) for a layout motif (like a responsive site or dashboard app).

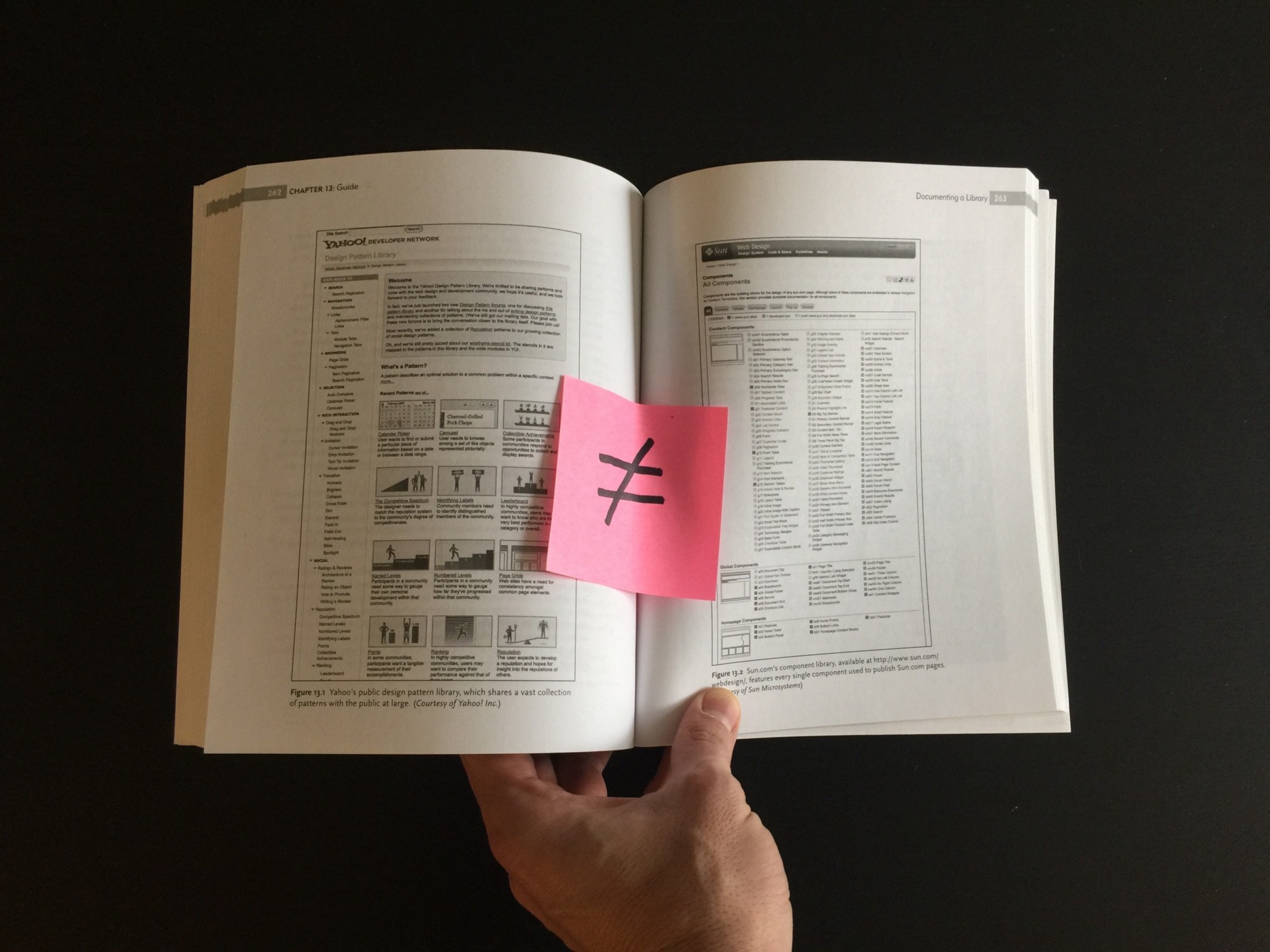

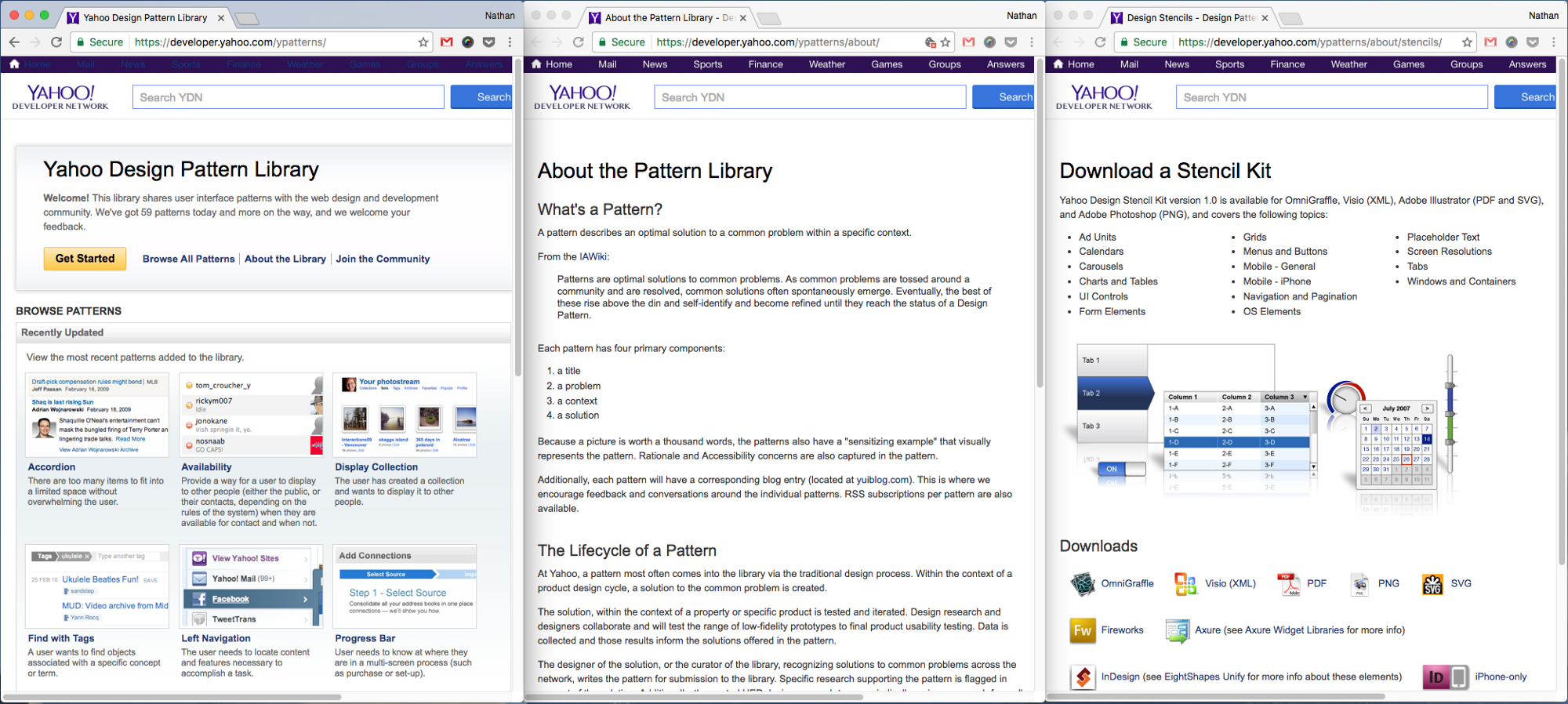

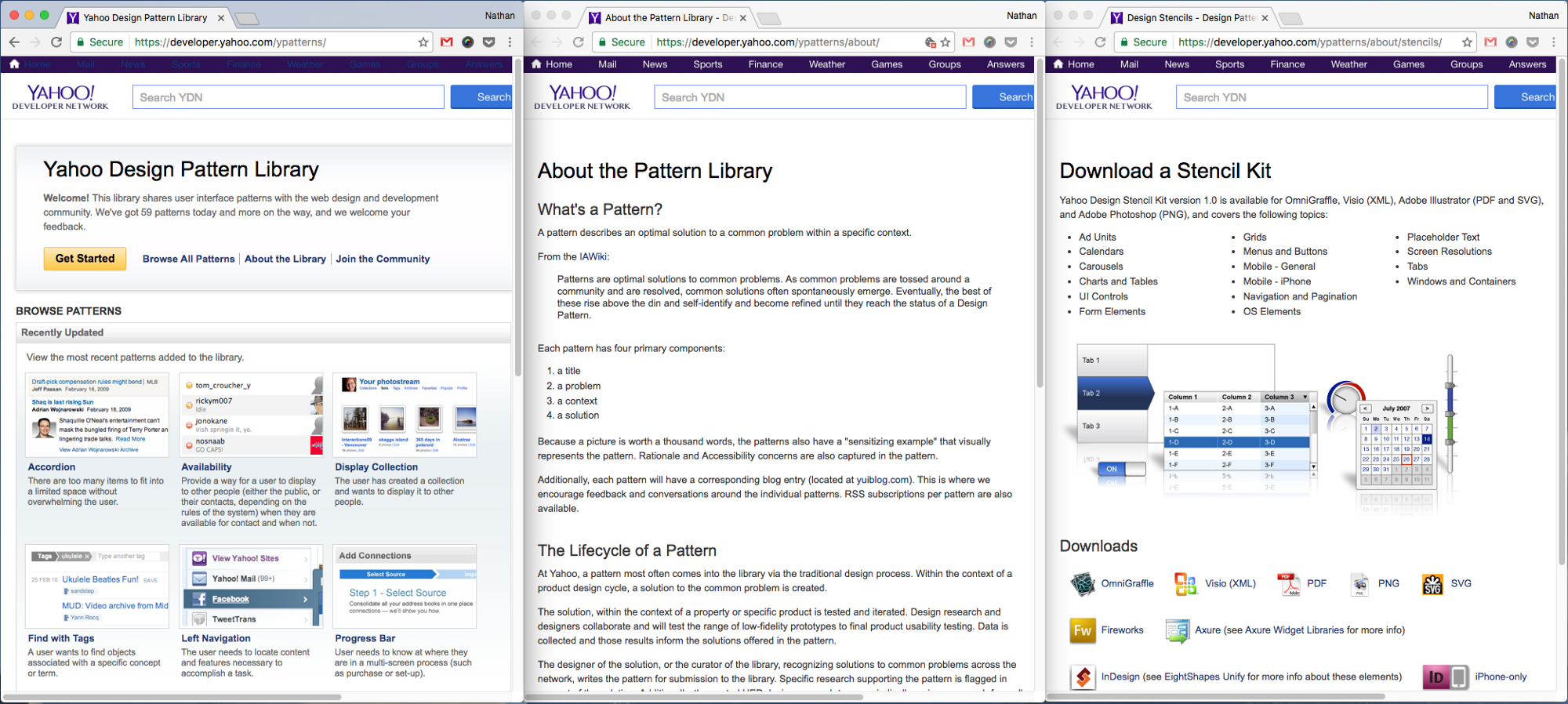

In the mid-2000’s, Yahoo’s massive design organization released their pattern library to the public.

Grounded by pioneering work of Jenifer Tidwell, luminaries like Erin Malone, Christian Crumlish, and Bill Scott contributed to the library that took at least my community (information architects) by storm. Erin wrote up their whole process on boxesandarrows.com. It’s processes and considerations are familiar to today’s design system makers. Many revered Yahoo then as they revere Salesforce Lightning and Google Material now.

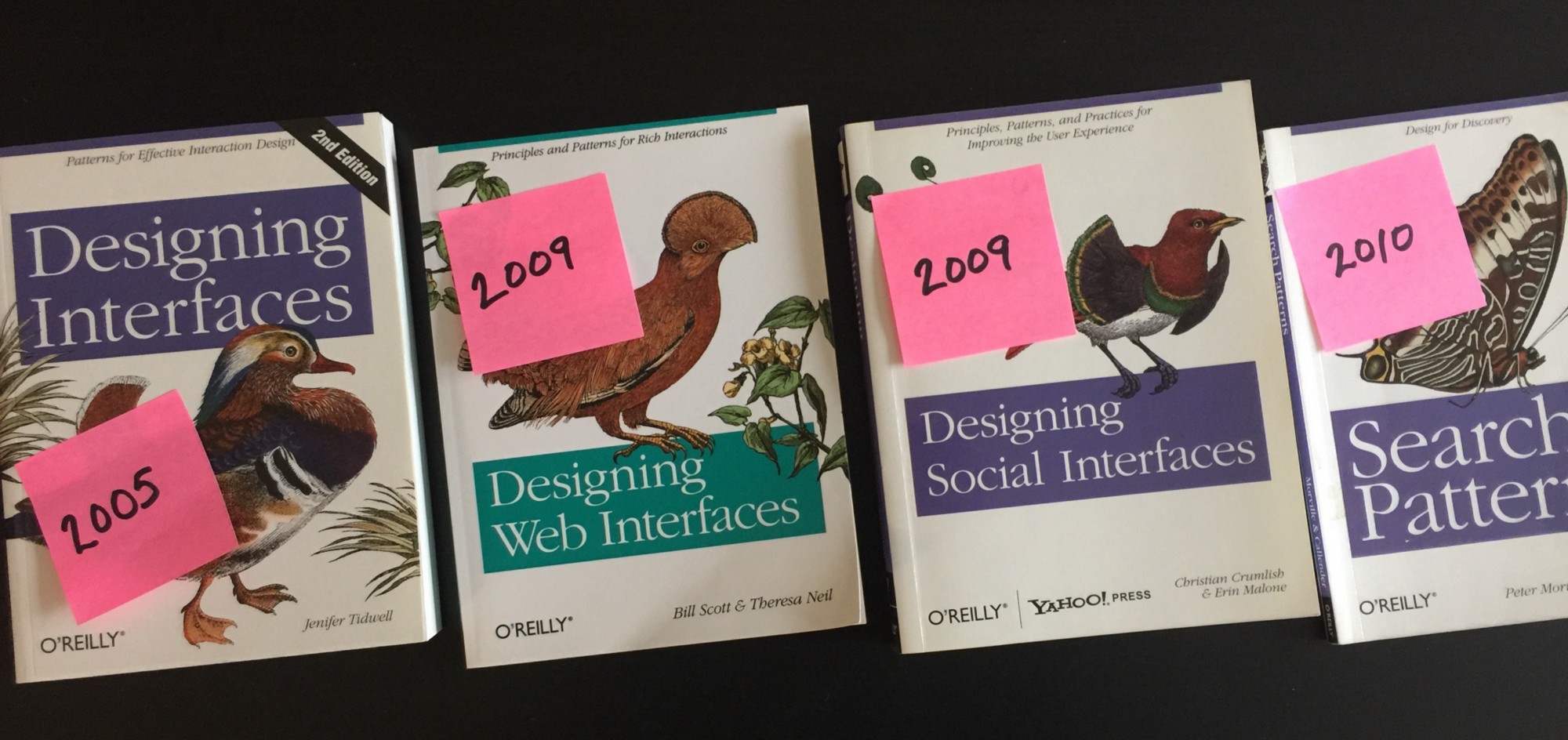

As the decade closed, many more libraries emerged and books provided in-depth pattern catalogs from a variety of perspectives:

Yahoo’s pattern library was a watershed moment as my career careened into components, patterns, and systems. It coincided with my first large scale library experience at sun.com from 2006–2010. Sun’s library was the most sophisticated library I’ve ever contributed to. However, those things we made at sun.com – and what so many teams make now – weren’t patterns in the formal sense.

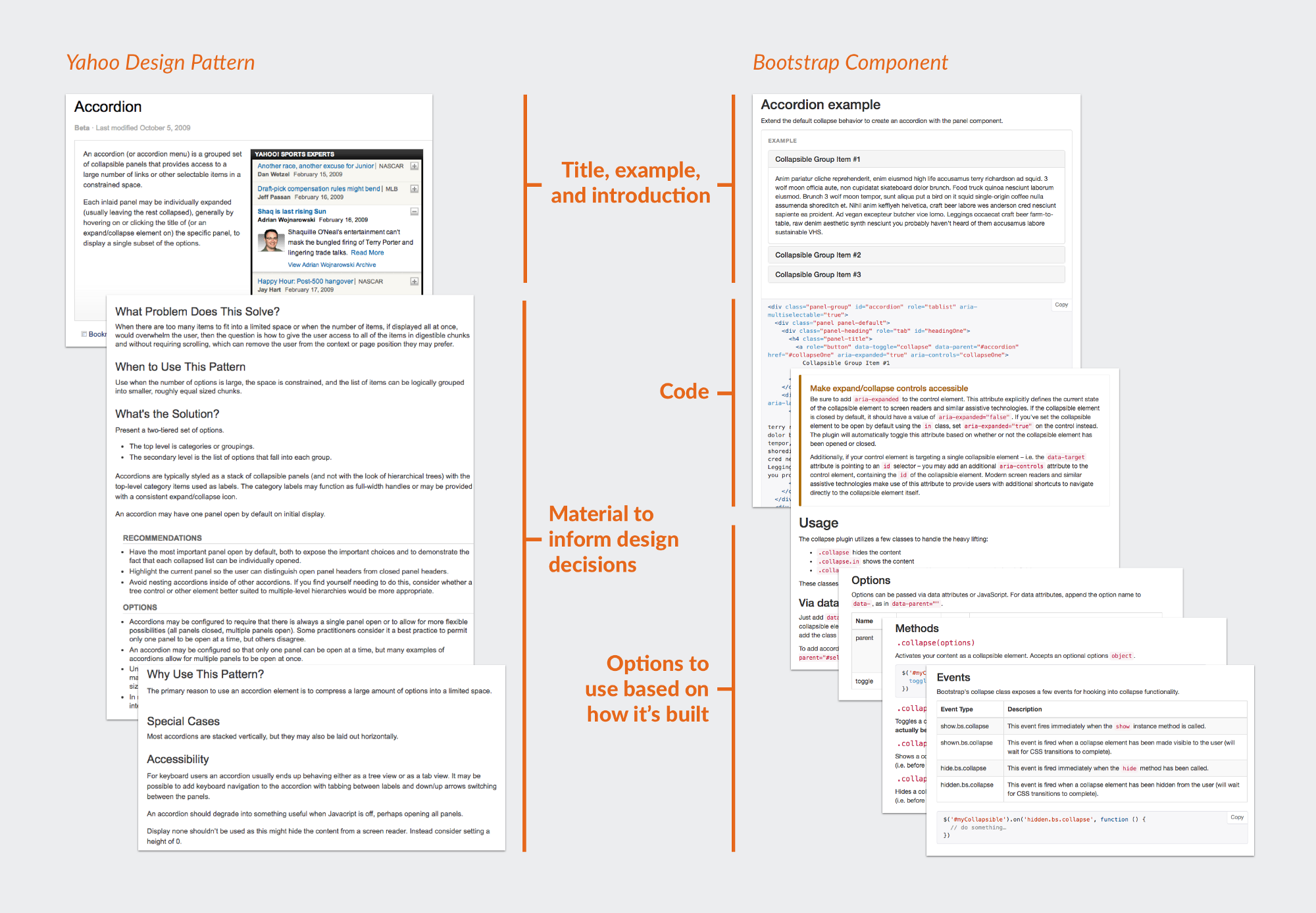

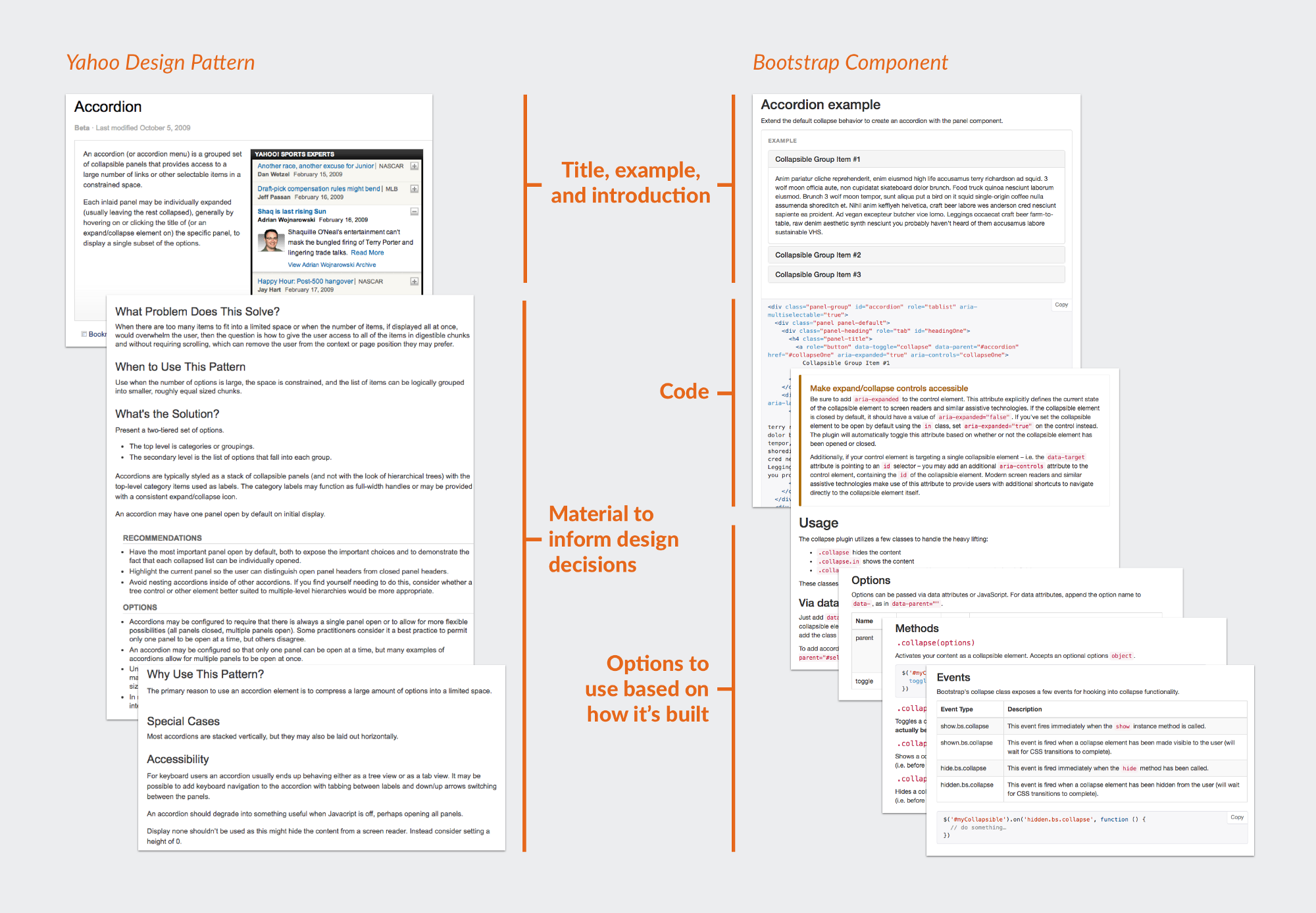

In Modular Web Design, I describe that components are designed and built in code, ready for reuse by plopping in a sketch file or HTML page, patterns are abstract, principled guidance applied as you design and build.

Components are how something DOES work , inclusive of tradeoffs and constraints realized through a build process. Patterns describe how something SHOULD work under preferred conditions and suggestions of how to cope with tradeoffs.

Components are an interface chunk to be added to an overall layout. whereas patterns may be UI or a variety of other things , like a behavior, flow, application motif or something else.

Completed components exhibit a visual language in polished, precise detail, yet patterns are independent of any particular skin and flexibly adapts across any visual language.

In Modular Web Design, Christian Crumlish (one time curator of the Yahoo pattern library) reinforced this nature of this distinction at Yahoo too. The public pattern library was related to but distinct from a ONE universal components library applied in-house across 80–90% of Yahoo’s product portfolio at the time.

Time passed, and things got quiet on the pattern front. Really quiet. Other stuff was going on.

In 2010, Ethan wrote a responsive web design thing. HTML & CSS increased in power and simplicity simultaneously. Designers began prototyping and building in code (and arguing about unicorns).

As a result, design-oriented and architecturally inclined minds began to organize front-end assets in maintainable libraries. Bootstrap hit, as did Foundation. Anna Debenham wrote about building and maintaining living guides. Mailchimp shared their UI Patterns. Brad Frost got atomic and worked with a team to launch PatternLab. System of style and components exploded, but “traditional” patterns didn’t follow along.

Where does this leave us? Many use patterns and components interchangeably as synonyms. Others explain “ patterns are complex components, arranged together, right?” Many can’t really say. Yet, a few high-profile libraries, like Google Material, strictly delineate the two.

I would spend energy distinguishing the two. But explaining abstract things is tiresome. Naming is hard. I moved on.

Folks are talking patterns again. In 2016, many of my clients began elevating (traditionally defined) UX Patterns for early system work. Still a lower priority relative to style and components, pattern interest is yet on the rise.

My conversations indicate this interest is due to:

Conclusion? System teams should invest in patterns too. Obviously, right?

Not so fast.

I adore Google Material’s collection. I find inspiration in GE Predix’s expansion into patterns of flows and apps. But those enterprises are massive!

Most teams and organizations I serve are one or two orders of magnitude smaller than that. Therefore, when pattern patter arises I’ll advise a cautious, more deliberate pattern investment because:

Don’t get me wrong, I value patterns. It’s just not that I’ve found a justifiable return on investment in creating a reasonably sized pattern library in-house.

On the other hand, I encourage small-to-medium size teams to compose just the most essential patterns unique to their customer experience:

To these companies, such a moment is fundamental. A pattern provides a way forward to a consistent experience across such an arc of the interaction whether applied on web, iOS, Android, or Windows.

However, start with one. And when you find success, be wary of setting expectations that an essential pattern signals a vast library next.

Patterns, if written well, probably don’t apply just to your team or even just your company. Well written patterns probably apply to everyone, everywhere, doing what we do.

In the latter part of the last decade, lots of endeavoring designers published their own libraries. Now, there’s a vibrant, engaged system community and tools where we could work together to write patterns we all benefit from. Is now the moment for a community to dive into UX Patterns? I’m not convinced, but I’m open minded.

Plus, Alexander didn’t write A Pattern Language for a client, but for an architecture community. A book for everyone.

In “Pattern patter.”, Ethan Marcotte writes yearningly for more design patterns in our practice. For now, many teams build libraries reusable components. However, these libraries usually lack thoughtful guidance to resolve myriad forces at play to compose interfaces effectively. Today’s libraries are (just) a kit of interface parts.

Ethan hints at the gap between reusable snippet and principled guidance. The call for more patterns, in my opinion, it misses a point. Those “pattern” snippets aren’t patterns at all. At least not in the formal sense. Those snippets are components. And conflating the two confuses and clouds our judgment on why in-house teams don’t pursue patterns much anymore.

Let’s trace pattern history to understand the difference.

In learning patterns, designers immediately encounter Christopher Alexander’s inspirational A Pattern Language (1977).

The book is required reading (or browsing, since it’s THICK) for any aspiring design librarian. The book lays out myriad patterns — Arcades, Sequence of Sitting Spaces, Six-Foot Balcony, and 253 others — as a language options to ground sound architectural designs and decision making.

Alexander’s catalog sets a content model for each pattern we emulate today:

You can trace Alexander’s influence into software engineering with Design Patterns:Elements of Reusable Object Oriented Software (1994) by Gamma, Helm, Johnson, and Vlissides.

Design Patterns quotes Alexander’s definition of a pattern:

<div class="escom-pull-quote escom-pull-quote--light">

<div class="escom-pull-quote__the-quote">

Each pattern describes a problem that occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, <strong>without ever doing it the same way twice</strong> (emphasis added).

</div>

<div class="escom-pull-quote__attribution">

Chrisopher Alexander

</div>

</div>

The book then differentiates patterns from the components of today’s “living style guides:”

<div class="escom-pull-quote escom-pull-quote--light">

<div class="escom-pull-quote__the-quote">

Design patterns are not about designs such as linked lists and hash tables that can be … reused as is. Nor are they complex, domain-specific designs for an entire application or subsystem. The design patterns in this book are descriptions … that are [then] customized to solve a general design problem in a particular context.

</div>

<div class="escom-pull-quote__attribution">

Christopher Alexander

</div>

</div>

Unlike patterns, components we use are already built for domain-specific reuse within a system. For example, a button is built for the web using HTML and CSS snippets to apply a visual language (like Material Design) for a layout motif (like a responsive site or dashboard app).

In the mid-2000’s, Yahoo’s massive design organization released their pattern library to the public.

Grounded by pioneering work of Jenifer Tidwell, luminaries like Erin Malone, Christian Crumlish, and Bill Scott contributed to the library that took at least my community (information architects) by storm. Erin wrote up their whole process on boxesandarrows.com. It’s processes and considerations are familiar to today’s design system makers. Many revered Yahoo then as they revere Salesforce Lightning and Google Material now.

As the decade closed, many more libraries emerged and books provided in-depth pattern catalogs from a variety of perspectives:

Yahoo’s pattern library was a watershed moment as my career careened into components, patterns, and systems. It coincided with my first large scale library experience at sun.com from 2006–2010. Sun’s library was the most sophisticated library I’ve ever contributed to. However, those things we made at sun.com – and what so many teams make now – weren’t patterns in the formal sense.

In Modular Web Design, I describe that components are designed and built in code, ready for reuse by plopping in a sketch file or HTML page, patterns are abstract, principled guidance applied as you design and build.

Components are how something DOES work , inclusive of tradeoffs and constraints realized through a build process. Patterns describe how something SHOULD work under preferred conditions and suggestions of how to cope with tradeoffs.

Components are an interface chunk to be added to an overall layout. whereas patterns may be UI or a variety of other things , like a behavior, flow, application motif or something else.

Completed components exhibit a visual language in polished, precise detail, yet patterns are independent of any particular skin and flexibly adapts across any visual language.

In Modular Web Design, Christian Crumlish (one time curator of the Yahoo pattern library) reinforced this nature of this distinction at Yahoo too. The public pattern library was related to but distinct from a ONE universal components library applied in-house across 80–90% of Yahoo’s product portfolio at the time.

Time passed, and things got quiet on the pattern front. Really quiet. Other stuff was going on.

In 2010, Ethan wrote a responsive web design thing. HTML & CSS increased in power and simplicity simultaneously. Designers began prototyping and building in code (and arguing about unicorns).

As a result, design-oriented and architecturally inclined minds began to organize front-end assets in maintainable libraries. Bootstrap hit, as did Foundation. Anna Debenham wrote about building and maintaining living guides. Mailchimp shared their UI Patterns. Brad Frost got atomic and worked with a team to launch PatternLab. System of style and components exploded, but “traditional” patterns didn’t follow along.

Where does this leave us? Many use patterns and components interchangeably as synonyms. Others explain “ patterns are complex components, arranged together, right?” Many can’t really say. Yet, a few high-profile libraries, like Google Material, strictly delineate the two.

I would spend energy distinguishing the two. But explaining abstract things is tiresome. Naming is hard. I moved on.

Folks are talking patterns again. In 2016, many of my clients began elevating (traditionally defined) UX Patterns for early system work. Still a lower priority relative to style and components, pattern interest is yet on the rise.

My conversations indicate this interest is due to:

Conclusion? System teams should invest in patterns too. Obviously, right?

Not so fast.

I adore Google Material’s collection. I find inspiration in GE Predix’s expansion into patterns of flows and apps. But those enterprises are massive!

Most teams and organizations I serve are one or two orders of magnitude smaller than that. Therefore, when pattern patter arises I’ll advise a cautious, more deliberate pattern investment because:

Don’t get me wrong, I value patterns. It’s just not that I’ve found a justifiable return on investment in creating a reasonably sized pattern library in-house.

On the other hand, I encourage small-to-medium size teams to compose just the most essential patterns unique to their customer experience:

To these companies, such a moment is fundamental. A pattern provides a way forward to a consistent experience across such an arc of the interaction whether applied on web, iOS, Android, or Windows.

However, start with one. And when you find success, be wary of setting expectations that an essential pattern signals a vast library next.

Patterns, if written well, probably don’t apply just to your team or even just your company. Well written patterns probably apply to everyone, everywhere, doing what we do.

In the latter part of the last decade, lots of endeavoring designers published their own libraries. Now, there’s a vibrant, engaged system community and tools where we could work together to write patterns we all benefit from. Is now the moment for a community to dive into UX Patterns? I’m not convinced, but I’m open minded.

Plus, Alexander didn’t write A Pattern Language for a client, but for an architecture community. A book for everyone.

EightShapes can energize your efforts to coach, workshop, assess or partner with you to design, code, document and manage a system.