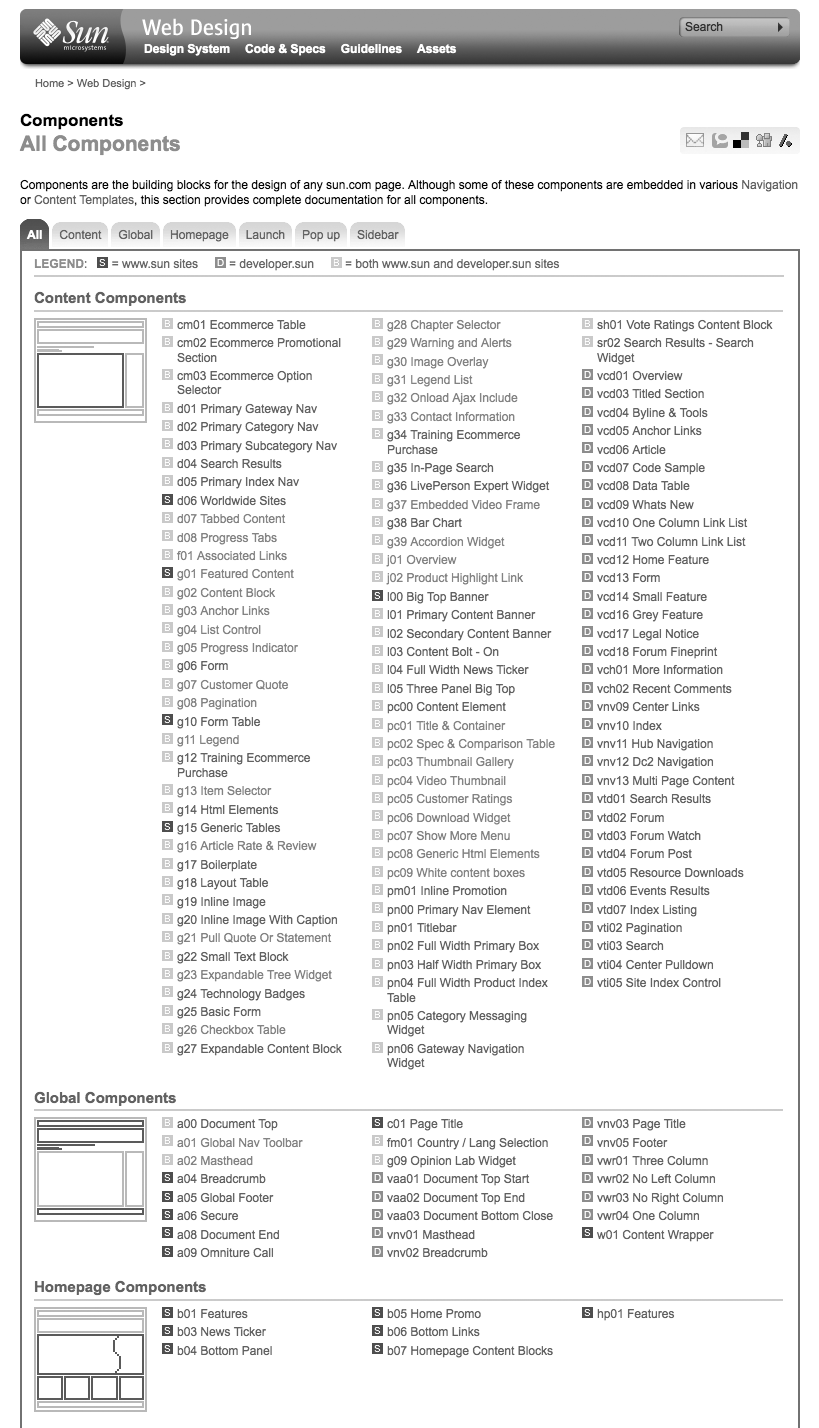

Back in the day, design systems were pretty easy to understand.

My day was a cool afternoon in September 2006, and I’d just immersed myself as a designer using Sun.com’s living style guide (we called it a component library, for the record). Even by today’s standards, that system remains the most formidable, mind-blowing web-based component library I’ve ever seen: 1,000s of component variations, each comprised of modular HTML, CSS, and JavaScript goodness.

The library was made by one unicorny overlord (before unicorns were a thing) with help from another front end dev. They supported code and people making two products: a marketing site and a sibling developer’s documentation site. The overlord monitored needs across web efforts (including more peripheral web apps using the library), chose what to design and build how he wanted it designed and built, and released it monthly. The library had a budget, and the program was predictable in cadence, resources and productivity.

Don’t like what’s in the library? Tough. Deal with it. The overlord decides.

And the overlord is busy. Dedicated, yes, to serving people like you. But busy using his practices to make parts for people usually more important than you and yours.

Fast forward to 2015. Raise your hand if you believe a design system — the people involved, products it applies to, parts it includes, and practices it employs — are slightly more complicated now. My hand is up. Really high.

Overlords don’t scale.

Instead, large organizations now embrace digital design at the scale of hundreds of designers working on countless products across web/native app, desktop/handset, internal/customer-facing, and other dimensions.

Now, more designers code. Now, more developers design. Product managers have hands dirty with everything. They all work tribally in teams spread throughout an enterprise. You can’t legitimately tell them what to do anymore. No one is that omnipresent, omnipotent or omniscient. You have to work together to build something bigger and cohesive.

So, how do you form a team that best helps you stay cohesive with a system? It depends on who you are and what you are capable of.

Nevertheless, modern design organizations are making their way from solitary teams making a library available or a centralized team serving disconnected products towards a more federated approach.

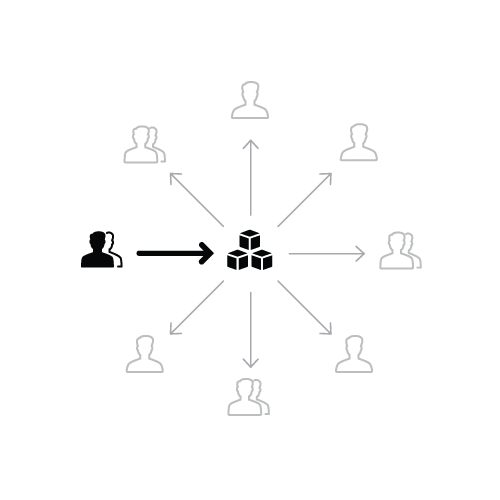

The overlord — a solitary team model — exists frequently in practice and has validity in some circumstances. Heck, Bootstrap itself is this model from the perspective of designers like me. As an archetype, it’s also inspired many follow suit and share their wares in-house.

It’s a noble enterprise, making one’s library available. The value is obvious, right? A production-grade codebase, based on an approved visual language, maintained and grown at another team’s expense.

Starting with an established asset library provides significant value to teams that lack the design and front-end development talent or capacity. It’s certainly worth a look, particularly if the library is modular enough to at least leverage parts that save some time.

This model is poor, however, for teams whose problems are only partially solved by an existing system, at best. For example, teams building transactional web apps connected to a product marketing site built with a robust library are different enough that considerable customization and/or extension is necessary.

Plus, sharing a library doesn’t mean its owners earn — or have to accept — drag on their own process or priorities. However altruistic their mindset, a solitary team’s primary motive is inward on their own product. The needs of adopting teams are a distraction from their cause.

This leaves other teams on their own, and if capable, building their own stuff. Let the divergent journey commence!

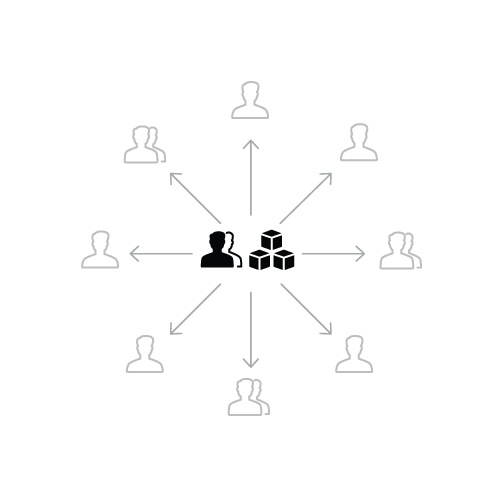

A centralized team supports the system with a dedicated group that makes and spreads decisions and parts for other teams to use but may not design any actual products. Maybe they’ve created the design language and system themselves, or maybe they are implementing a vision produced by an outside agency.

The centralized system team can:

However, centralized teams often lack:

Ultimately, a centralized team can provide a great service and create value in efficiency, consistency, and capacity. But be careful. Their position is tenuous, and their desire to prove their worth may undermine their effectiveness serving product teams that want to sustain their autonomy anyway.

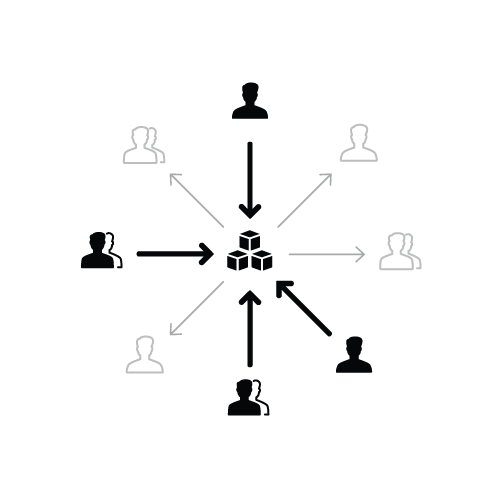

So, if solitary and centralized models don’t fit, there is a more complicated path to pursue, relevant for organizations of high-performing talent :

In recent years, systematic thinking of designers across platforms and product lines grown considerably. Google Design’s progress is the archetype. A small yet growing group of empowered designers formed what became Material Design using a “committee-by-design” approach.

Such a committee federates a system’s design direction to a representative, empowered subset of designers and leaders designated to collaborate on the system for a period of time.

They make design decisions collectively, even if only a subset — or others — record, build upon and communicate those decisions through artifacts like a living style guide.

It’s not open season; not everyone participates or gets a say. Instead, the federated group’s decisions propagate out to other product teams that leverage the outcome or ignore it at their own peril.

A federated team will:

Even so, that’s lots of cooks.

Plus, each designer’s retains autonomy for and an allegiance to their product team. Until a system has staying power, designers may limit their commitment, attend unpredictably, and even express honest, deep seated guilt even being away from their product team. To participate in this model, a designer must be able to convincingly transcend tribal affiliation for the greater good of a cohesive user journey, in how balance both their time and decisions.

A federated model also introduces practical challenges in decision making. Design discussions happen naturally, at a desk, in the hallway, at lunch, or in a Slack channel that passes other by. A pair may launch into a discussion that yields switching a secondary button style from outlined to gray. Then two others see that in Slack, debating its merits there. Another designer puts it in context in their iOS app, it looks boorish, and suddenly everyone is confused.

Each conversation yields insights, and even momentum, but no one keeps track or can recall the path that led to a decision (or, at least, the latest iteration). Individually relinquishing control becomes essential. Plus, teams must balance decisiveness and progression with pausing decisions of broader implications for when “everyone’s available to discuss it.”

When forming a federated team, there’s so many dimensions to consider, including who’s available? For how long? When do we need the system by? Who has the skills to identify and build the parts we need?

Over the past few years, my experiences suggest that considerations include a mixture of representation, discipline breadth, doers and shakers, and yes, that pesky investment in a central effort.

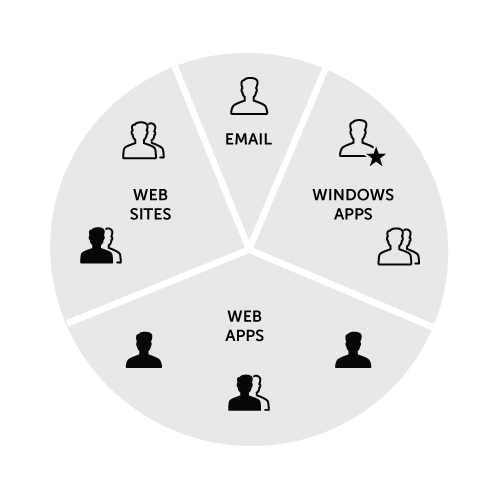

In a recent engagement for a small product software company, I was delighted to see sufficient UX and design involvement across web sites (for marketing and community engagement) and web-based app products. Responsibilities were well-understood, and a design language and key components had begun to stabilize.

My time with them convened system contributors in a war room for an intense week to hash out details and launch the system company wide, by week’s end.

The most delightful yet unexpected outcome? Proving how the system worked on Windows apps, the company’s cash cow. A respected developer from a flagship Windows app team brought his laptop and sat in the room. He worked tirelessly for days to apply the emerging design language to his app’s tired visual style. Seeing real screens based on real code converted the many other skeptical Windows app developers; developers that represented the vast majority of their portfolio. Sure, design improvement was obvious. But they now believed it could be done technically, too, by a person they trusted.

The breadth of a system team’s talent should mirror the system’s scope. Mature teams don’t get religious about discipline boundaries, enabling perspectives and inputs to richly overlap. Nevertheless, one federated team leveraged the particular set of skills of individuals to monitor:

This established a path of who to “Talk to..” for those outside system efforts. Internally, however, these individuals consistently blurred such boundaries when collaborating, encouraging each other to add whatever value they can, when they can.

The trio became known as the bizarre acronym UVI. Say it, out loud. It sounds ridiculous, right? Motivated to rid the world of really bad acronyms, I asserted successfully to inject a recently hired Director, Content Strategy as a fourth leader to up their game. Ahh, the bliss of a slightly more pleasant and apropos CIVX (using X for UX).

One large design organization intermingled directors (designers themselves, but managing the work of 10 to 30 other designers) with designers producing on flagship web and native products.

The directors brought exposure to a wide range of emerging designs on their teams. Sure, they weren’t producing design artifacts on a daily basis. But they sweat design details, like course correcting usage of a blue tint that muddied a background in a product outside their purview.

Directors were also great providers of talented yet idle staff for intense, short bursts of focused system work. For example, one core team Director made a designer available for a days effort to normalize a starter set of icons. This rock star iconographer lacked context of the wider mission but lent a hand, saving everyone from tedious iteration over weeks or a vendor trying to prove themselves.

Effective federated teams distribute system decision making and doing across the management hierarchy, deferring decisions to talented leads and contributors mixed with the influence and decisiveness afforded to engaged directors and above.

Living style guides don’t build themselves. And all those (cheap) words and (expensive) illustrations, examples, and code snippets don’t just magically appear on webpages that show everyone else how they can do things.

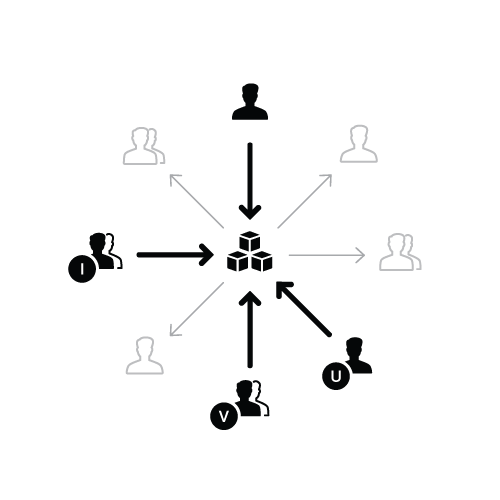

As a design system stabilizes, every team I’ve observed has designers that do build, document and sustain it, and designers that can’t or say they want to but don’t. As decisions — a primary button’s color, a modal’s close icon, a nav bar’s responsiveness —stabilize, teams need to figure out how to fluidly and continuously communicate that change.

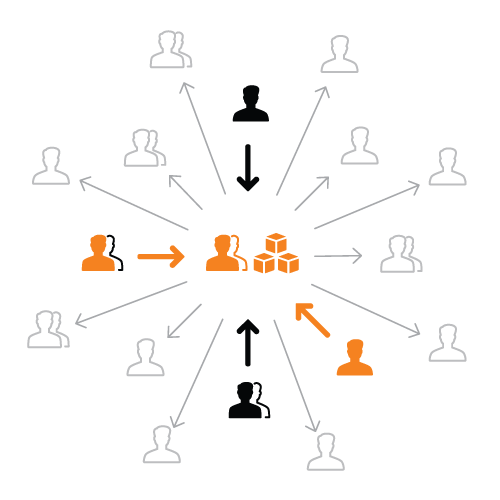

Good teams have a clear sense of who documents these decisions and how they are communicated. These contributors (depicted in orange) author guidelines, build components in code, update design tool templates, and do so much more keep the system alive.

High-performing teams establish platforms (such as github.com repositories and other content publishing tools) that enable an array of individuals to continuously evolve a system’s definition.

But, alas, some teams don’t have such platforms. More often, the individuals making decisions in a federated model aren’t always available enough to write them down.

Yes, a federated team needs a centralized component of staff dedicated enough to the cause.

Leaders create space for doers to get the job done. They ensure there’s staff for whom the library is a prioritized responsibility of or only part of their job. Without that fine work, that living style guide can seems quite dead — or at least unconscious — ten months on.

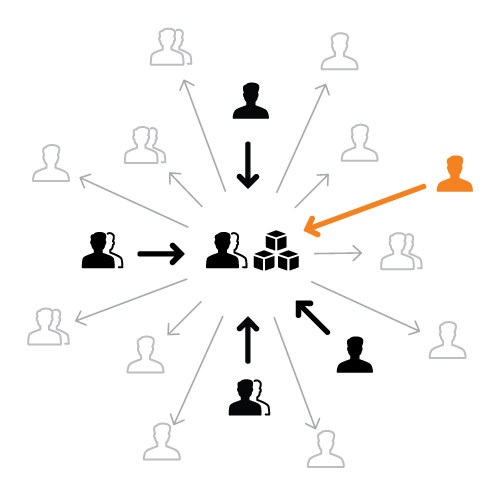

Federated teams strongly discourage exclusivity once the system starts to spread. Instead, they embrace peripheral designers willing (and able) to contribute.

Such contributions can trigger a reciprocal incentive: autonomy. Jon Wiley claims that during Material Design’s formative period, the more that peripheral designers would engage and embrace the mission, the more the core team would be tolerant of and interested in divergent ideas.

Watch for those designers with valuable ideas — and time — that eagerly want to get on board. As they signal interest, be willing to invest time in critiquing and evaluating their exploration to see how they fit.

Undoubtedly, there are other variants of centralizing and federating decision making around and support for a design system. What’s in your system?

EightShapes can energize your efforts to coach, workshop, assess or partner with you to design, code, document and manage a system.