An enterprise usually has many concurrent design systems. Separate groups chart paths loosely aware or even willfully ignorant of what others do. Many systems isn’t necessarily bad. Different programs may support different experiences and teams with different tools, and that’s ok.

Other times, systems keep experiences and teams apart. Unjustifiable inconsistency. Varying quality. Unmistakable redundancy. “We can do better,” an enterprise leader may say, “designing at scale.” And so they ponder:

Consolidation takes effort, time, and an emotional capability to relinquish (some) control. Heretofore independent systems may resist this uncomfortable change. So an approach to consolidation is best shared, rational, and yet also decisive. First, share an understanding of how each system arose. Second, rationalize the features, outputs, and practices on offer. Finally, define a consolidated identity and how it comes together.

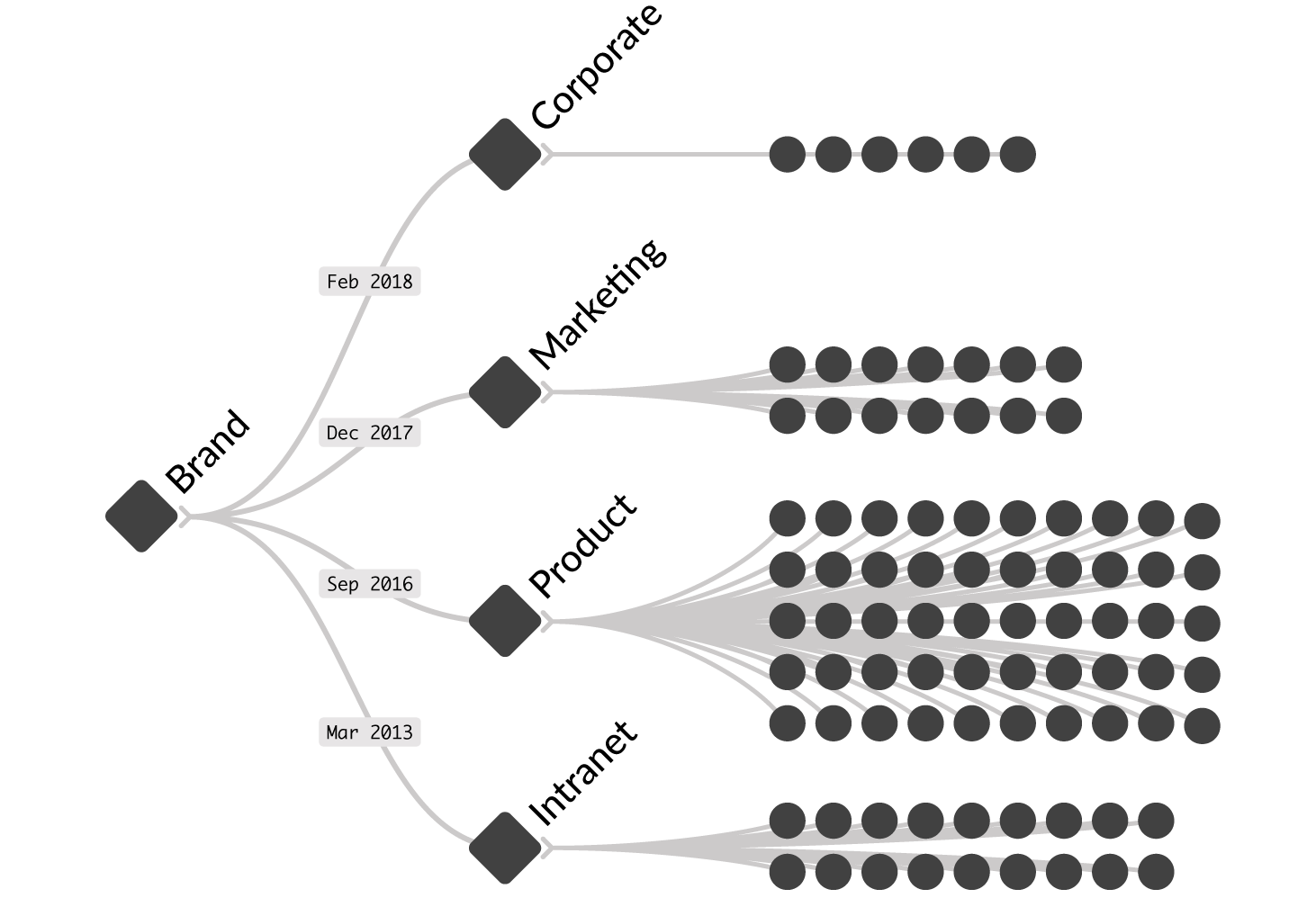

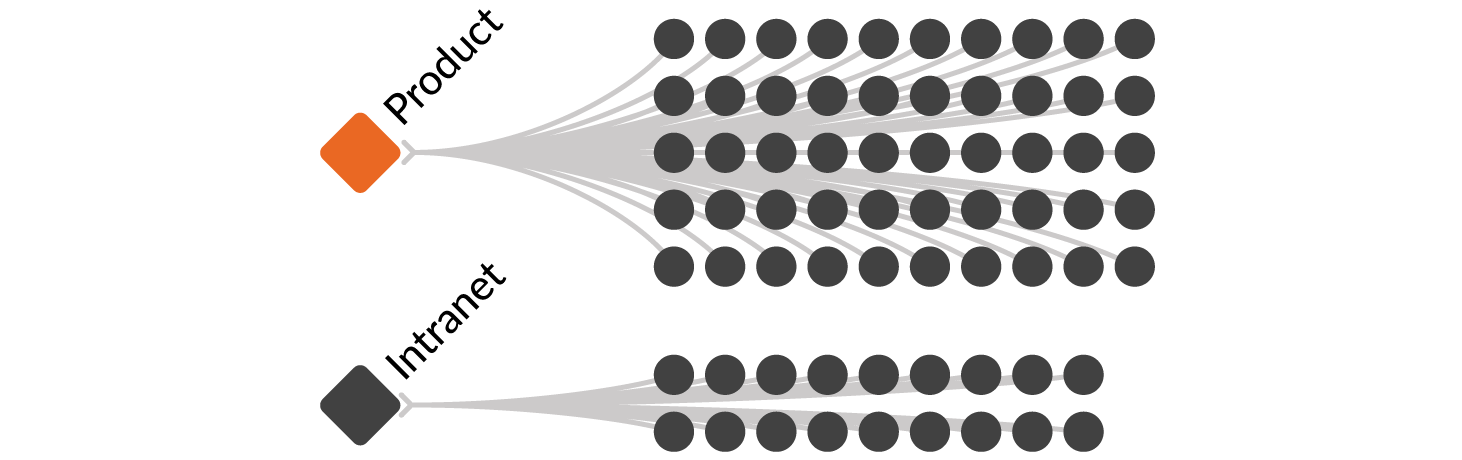

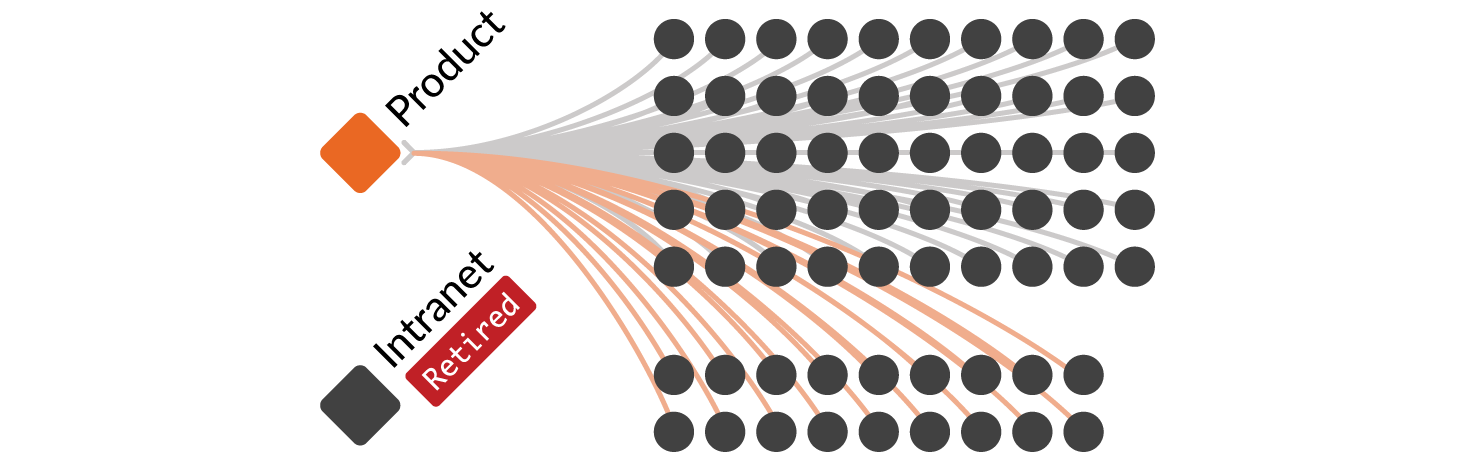

Products (here, a circle) adopt systems (here, a diamond) to efficiently and consistently compose their experience.

Across an enterprise, disparate systems can arise separate by myriad boundaries of teams, organization units, and platforms.

For example, systems can mirror organizational boundaries, such as:

While distinct systems, outsiders assume they share a common visual language inherited from Brand. Or, at least the logo, right? Not always. Inspection reveals massive discrepancies. One experience touts modern typography sourced from Brand in 2018. An archaic internal toolset from 2013 still rocks Verdana. It’s as if they are from separate companies. If you’ve worked at a company of any scale, you’ve lived this.

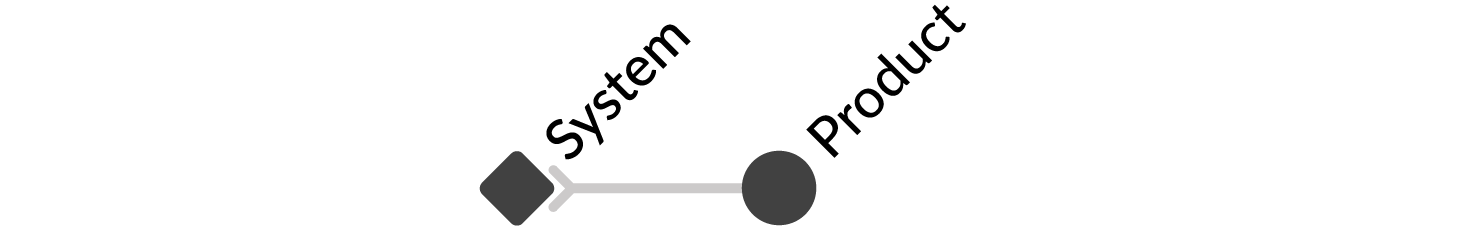

Larger entities — think the size of Microsofts, Amazons, IBMs, GEs, or any of the large banks — may replicate such system divisions across lines of business.

In other cases, lines of business also create boundaries, such as a bank’s groups and apps for credit card, banking accounts, and loans. Leaders in design, product and engineering may be on their consolidation journey, having consolidated some (like credit card and banking) while others (loans and institutional) lag behind.

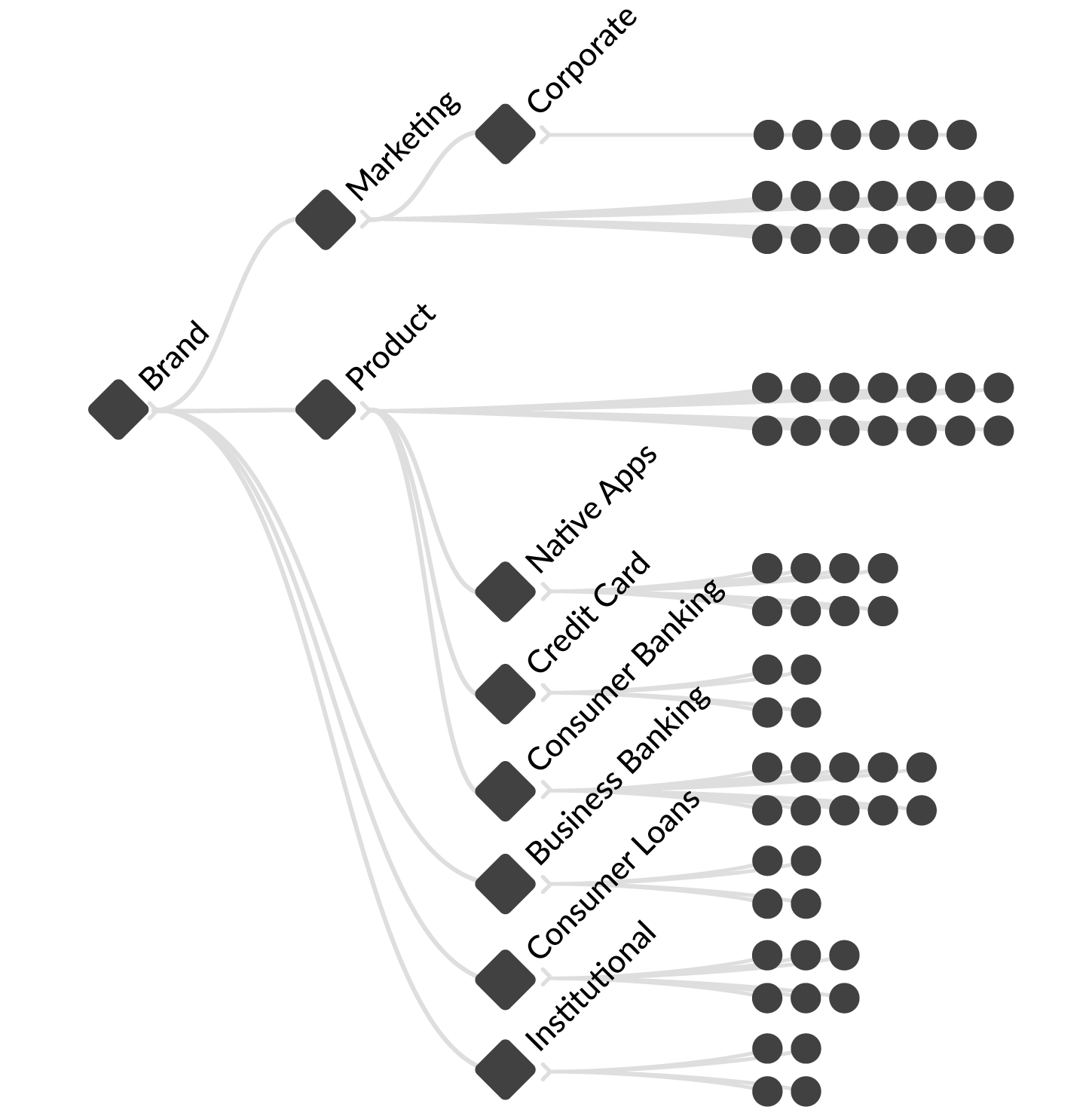

Distinct systems can also emerge due to a fairly basic premise:

Maybe native design conventions differ from the better-funded web system. Or, there’s a belief that “Employee tools have different needs than customers. Therefore, we need a different visual style and components.” Flat out, maybe it’s thinly-veiled hubris: their system isn’t good enough for our stuff. Digging into this more subjective and often emotional divisiveness is important.

Well-intentioned system teams serving distinct portfolios do try to “stay in touch” and “share best practices.” Yet apart from a meeting here and a hallway conversation there, nothing comes to pass. Are they sharing outputs like code libraries, documentation, design asset libraries? Not even close.

If you are considering consolidating, the first step is compare and rationalize differences. Your objective: help makers, customers, and sponsors get a sense of how things differ and could change as a result.

To start, compare features of visual style, UI components, and other categories. Identify what features exist, how they are disseminated (as code and design assets), and depth of documentation of each part.

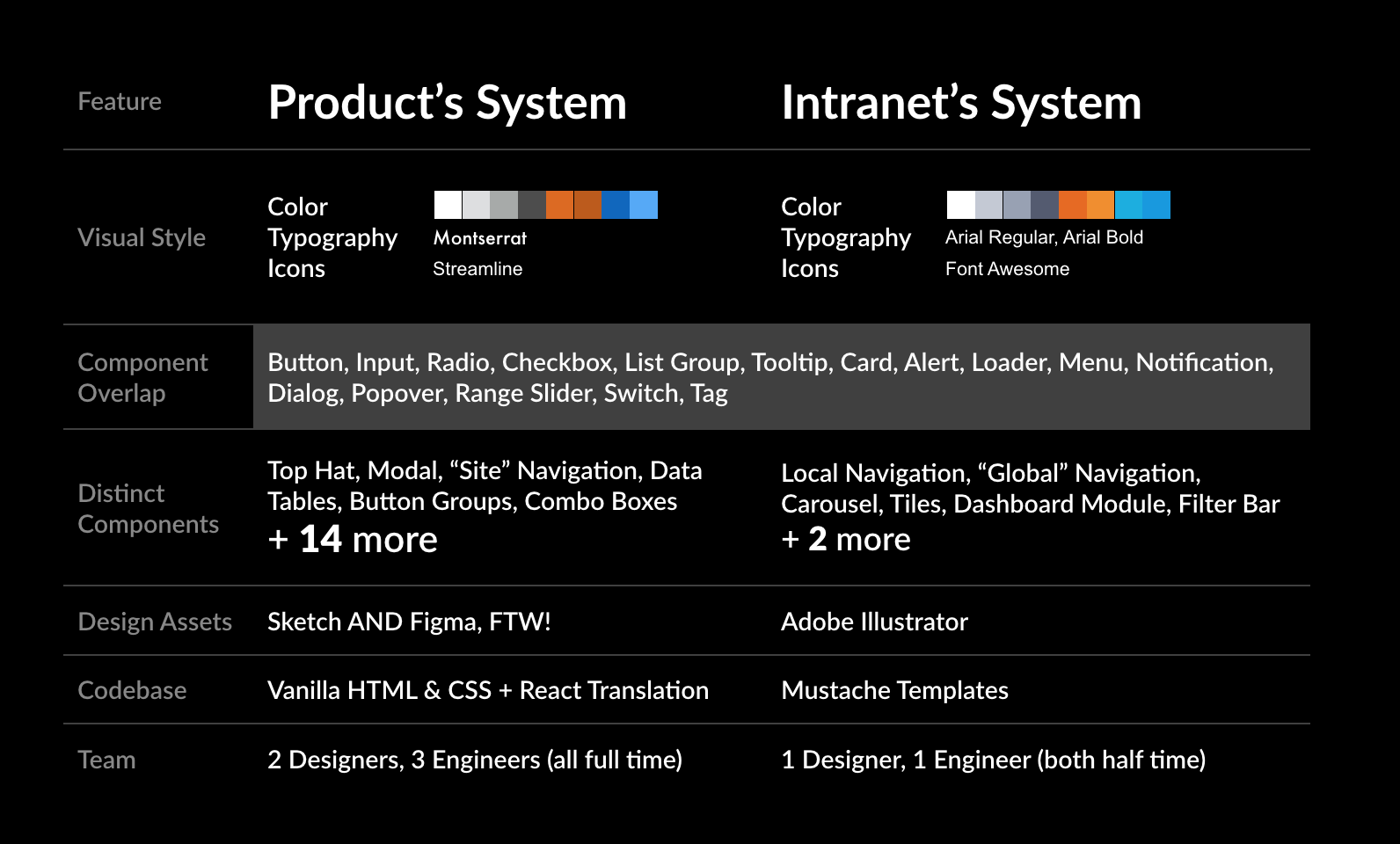

For example, a Product group’s system may be more robustly featured and funded. On the other hand, Intranet’s system may be less mature, minimally funded. In that case, a high-level comparison would communicate:

Systems aren’t just features. You must also evaluate how each system gets work done, expressed through the teams, processes, and depth of adoption already established. So also compare:

System histories and rationalization in hand, time to answer the big question: how do we consolidate and what — if any — systems survive it?

Sometimes, teams walk away from the table. They aren’t ready to yield the autonomy, established norms, and distinct goals they don’t share. Another big threat? Resistance to change among their adopting customers.

Takeaways: If adoption of a consolidated system isn’t likely, why bother ?Traditionally, slowly changing products (I’m looking at you, internal tools!) are less likely to prioritize what consolidation brings.

To avoid doing nothing, begin conversation with agreement that both portfolios intend to use a consolidated system, soon. Also, to push conversation past a “do nothing” impasse, leadership must care enough, mandate consolidation, and designate a system to serve — and expected to be used by — teams into the future.

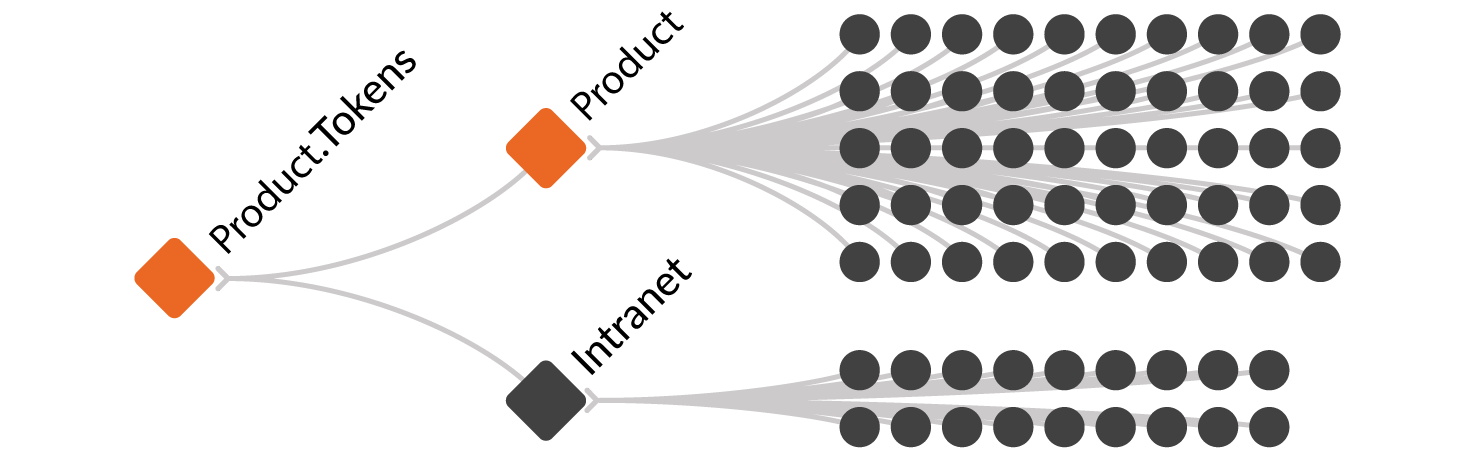

Complete consolidation may be too ambitious, yet teams could start with subsystem(s). Multiple systems with smaller connections — in code and collaboration — makes things more complicated. But start small, pilot sharing the foundational things, and see if it works.

Takeaways: It’s hard to stay connected, in agreement, and synchronized across boundaries without a long term commitment.

I’ve never seen a subsystem-only step occur, although I’ve discussed it with a few organizations. The approach appeals to sensibilities of separating concerns and making incremental progress. Yet change will be slow and and lack authoritative oomph. My role as outsider often leads to the harder, strategic question: are we really consolidating or not, and if so, how?

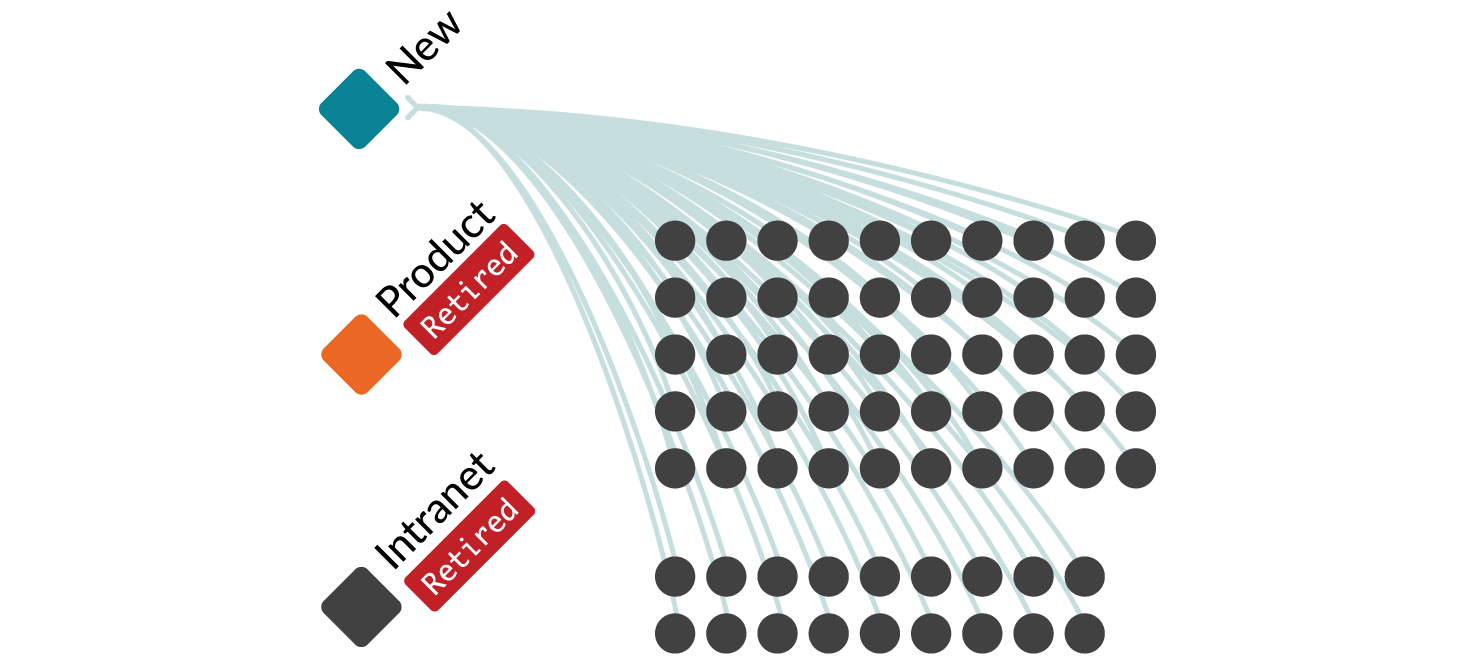

Instead of sustaining existing features from one or both systems, you may retire both as a reboot to something new. Blowing up the old and starting fresh, bigger may be triggered by an external force — an executive mandate, brand refresh, or tech replatform. Maybe all of the above.

Takeaways: Consolidation framed as a merger of equals raises complications. Decision-making is unclear. Everything is up for discussion. Without a considerable reboot leveling the playing field and really starting fresh, rationalization could dilute the value of both and integration becomes time-consuming. It’s expensive to reinvent from the ground up. Worse, every product’s change will take a long time. This is a difficult path to tread.

Rationalization often indicates a predominant choice. A stronger system. As such, the mindset shifts to acquisition: what must we add from the weaker to the stronger system to best support all customers?

When discussing an acquisition, ask the hard questions:

Takeaways: A stronger system’s success places them in a powerful position to dictate terms. Acquired systems may bring weaker tools, processes, capacity and commitments from their leaders. Yet their core features may still be strong, as is their emotional tie to them.

When talking mergers and acquisitions, “look into the books” of weaker system too. They may be looking for a way out, an existential lifeline, otherwise risking a fade into an abyss without a consolidation.

These imbalances makes consolidation conversations difficult. Your goal? Realizing the promise of a thriving practice serving more teams at scale. So time to exercise some leadership and management to make consolidation best serve your community!

EightShapes can energize your efforts to coach, workshop, assess or partner with you to design, code, document and manage a system.