I really like using Jira. I value the order it brings to the complicated chaos of making, curating, and contributing to design systems. I’m no Jira admin, and I ain’t no certified scrummaster. That said, I’ve brought enough order to design system chaos using Jira to share the durable approaches I’ve learned.

Others have their feelings about Jira, too. I don’t know how your enterprise uses Jira. I don’t know how your team wants to manage tasks. Every team is different: what’s been good for my teams may not work well for your teams. Most of my clients use Jira, but there are some that don’t. If you don’t, or if you use Jira differently, I hope the ideas presented here still help you.

I’ll start with how I approach starting a Project, add stories with good names (Summary) and organization (Epics), and iterate (Sprints) work over time and releases (Versions). Things will get complex as we break down work (Subtasks). Yet, all this data must lead us to coordinate efficiently in day-to-day ceremonies like the Grooming, Planning, and Standups. Let’s dig in.

To use Jira, you need a project instance. Avoid the hypocrisy of sidestepping conventions imperfect for your team (ahem, you are a design systems pro, so grow up!) by learning how your organization uses the tool.

When ready, create a project with the help of an admin, starting with a name.

Every Jira project needs a name (like Design System) and, more importantly, a namespace (like DS-). That namespace shows up everywhere: screens, comments, descriptions, emails, pull requests in Bitbucket (or similar), etc.

Examples here use DS- (for a generic design system). In real contexts, I’ll emulate the namespace used in CSS classes or web component prefixes that our users encounter in their work. For the Morningstar Design System, it’d be mds-. Once your project is setup and named, welcome to your clean, intimidatingly empty backlog.

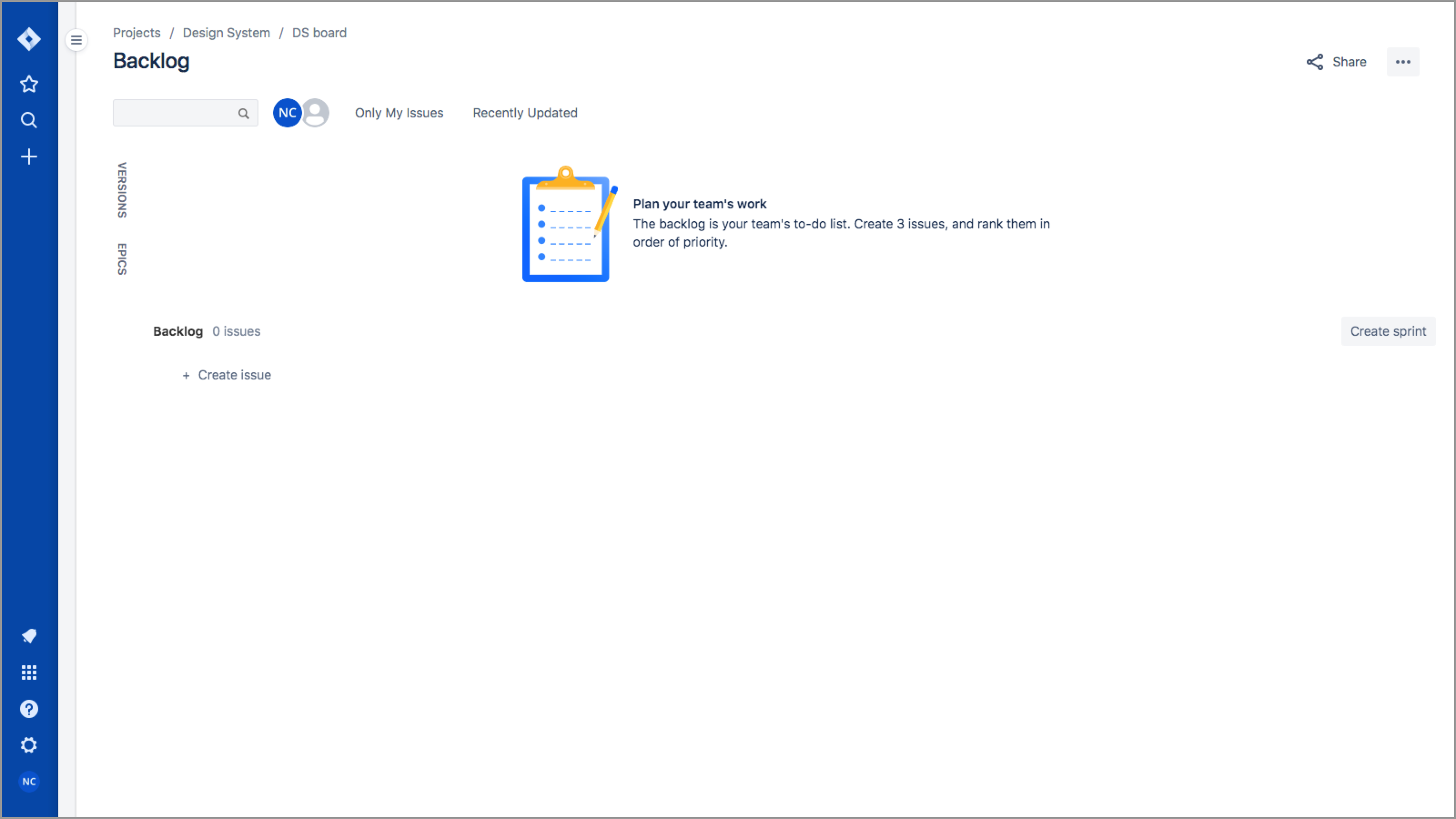

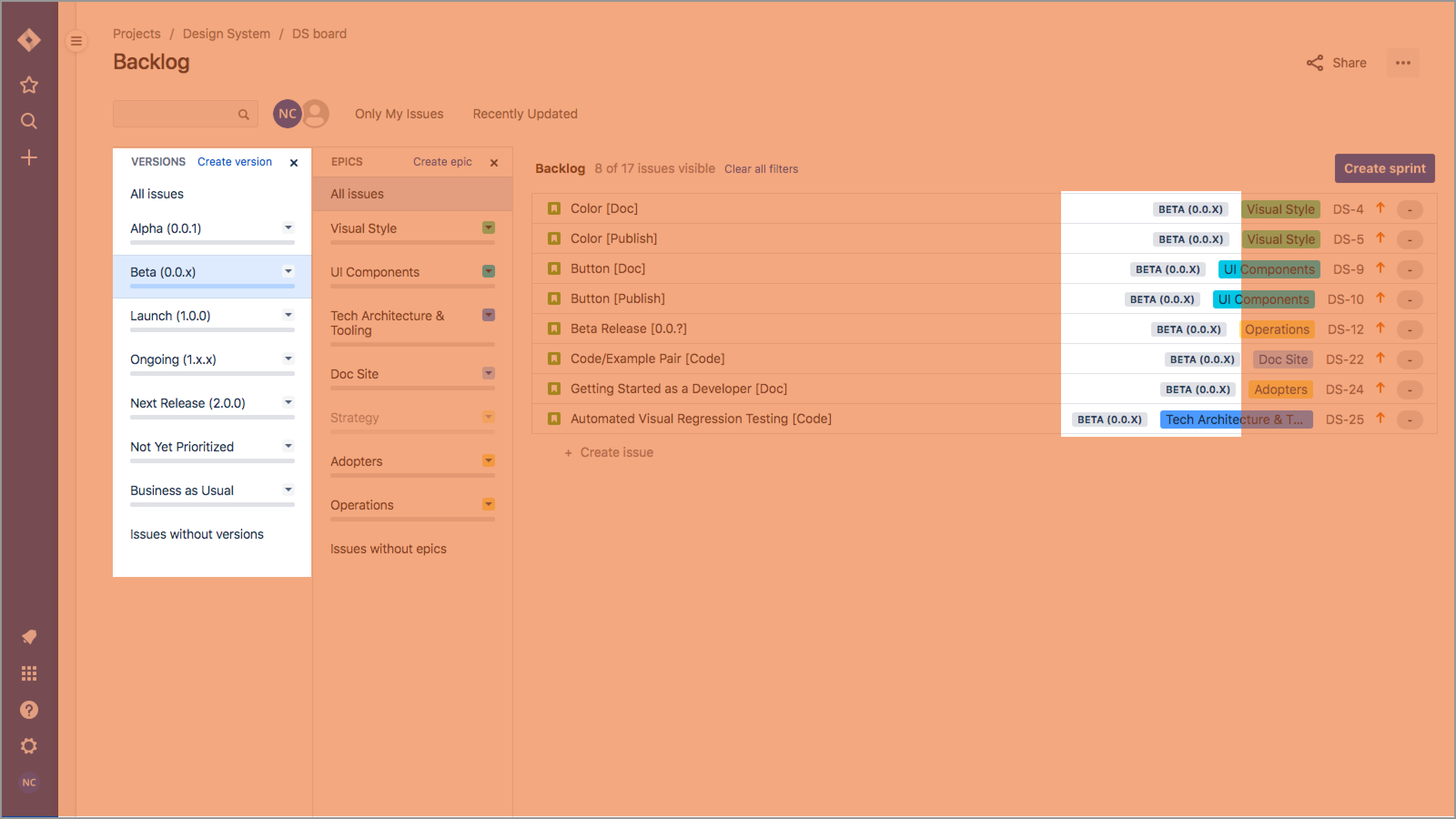

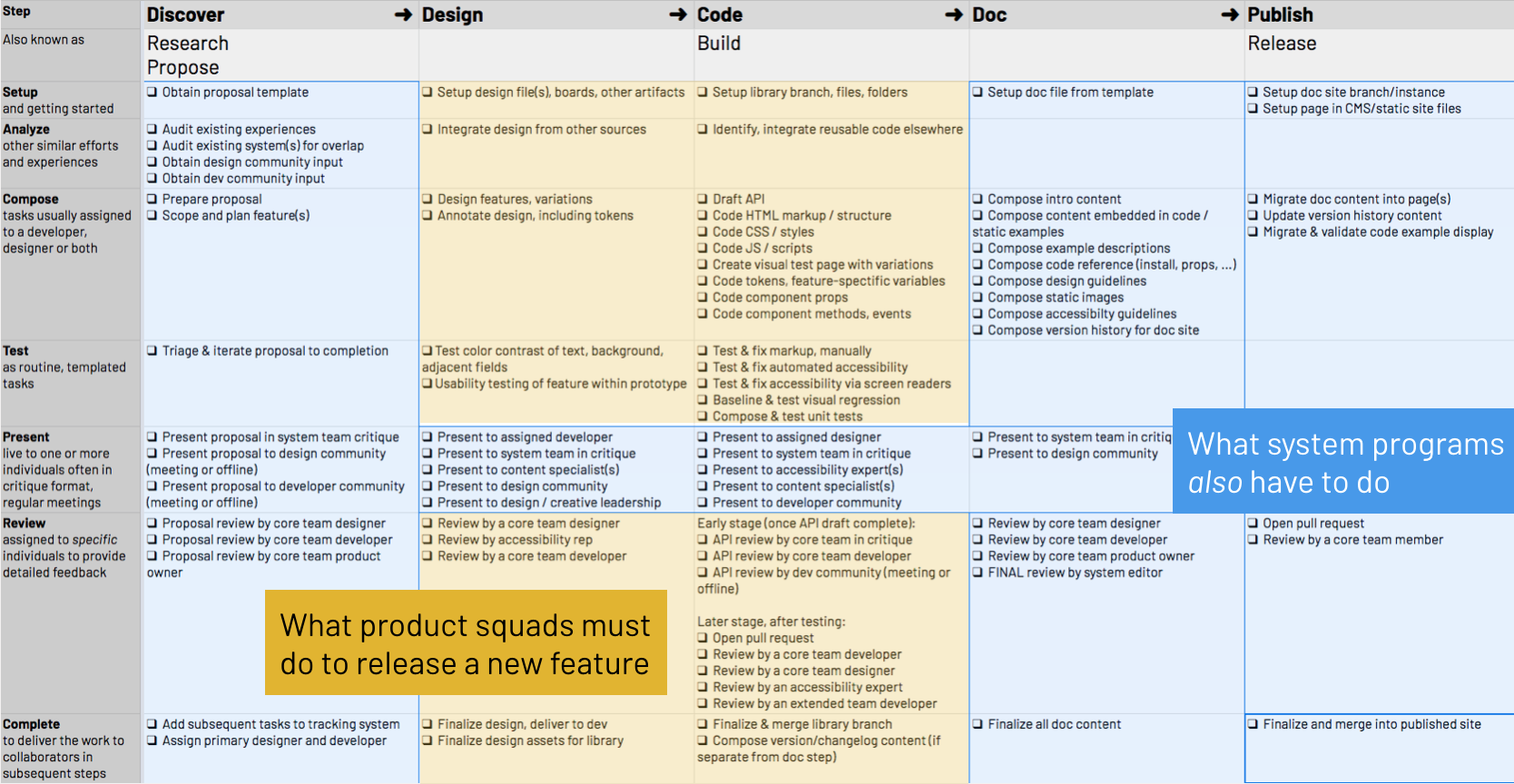

A design system backlog is rich with features we make, from visual style’s Color and Typography to a UI component library’s Icon, Button and Modal. Since 2016, my teams have been breaking down work per feature into repeatable steps: Propose (or Discover), Design, Code, Doc, and Publish as described in Design System Features, Step-by-Step.

![Jira backlog with feature stories (such as Color [Design]) and event-based stories (such as final workflow for a release)](/images/articles/using-jira-for-design-systems/2.png)

In Jira, each step per feature is represented by a separate top-level story, such as Color [Propose] (scoping the work), Color [Design] (iterating in Sketch or Figma ), Color [Code] (delivering mixins and tokens), Color [Doc], and Color [Publish].

Why multiple stories per feature? Feature delivery usually spans many sprints, each step ends with a clear definition of done, and steps are assigned to different team members, such as a designer for[Propose], [Design] and [Doc], and a developer for[Code] and [Publish].

Work isn’t just feature development. Work also includes predictable routines also tracked as stories, including:

Each of these are added regularly to and completed within a sprint, loaded with copious repeatable subtasks (see below).

All sorts of other work crops up: special research, strategic presentations, technical spikes, process documentation. These stories round out a backlog, comprising a non-trivial array of non-repeatable work. This work is difficult or impossible to model well, so we borrow conventions (like calling a process activities Code and Doc based on it’s outcomes) but acclimate and get comfortable with the rich heterogeneity of day-to-day reality too.

My pursuit of clarity (some say OCD) requires normalizing and improving story summaries that can be vaguely or imprecisely input by teammates. For example, I’ll often append a missing task type ([Propose], [Design], [Code], [Doc], [Publish], [Defect], etc). These small adjustments improve story scanability and consistency in Backlog and Active Sprint views.

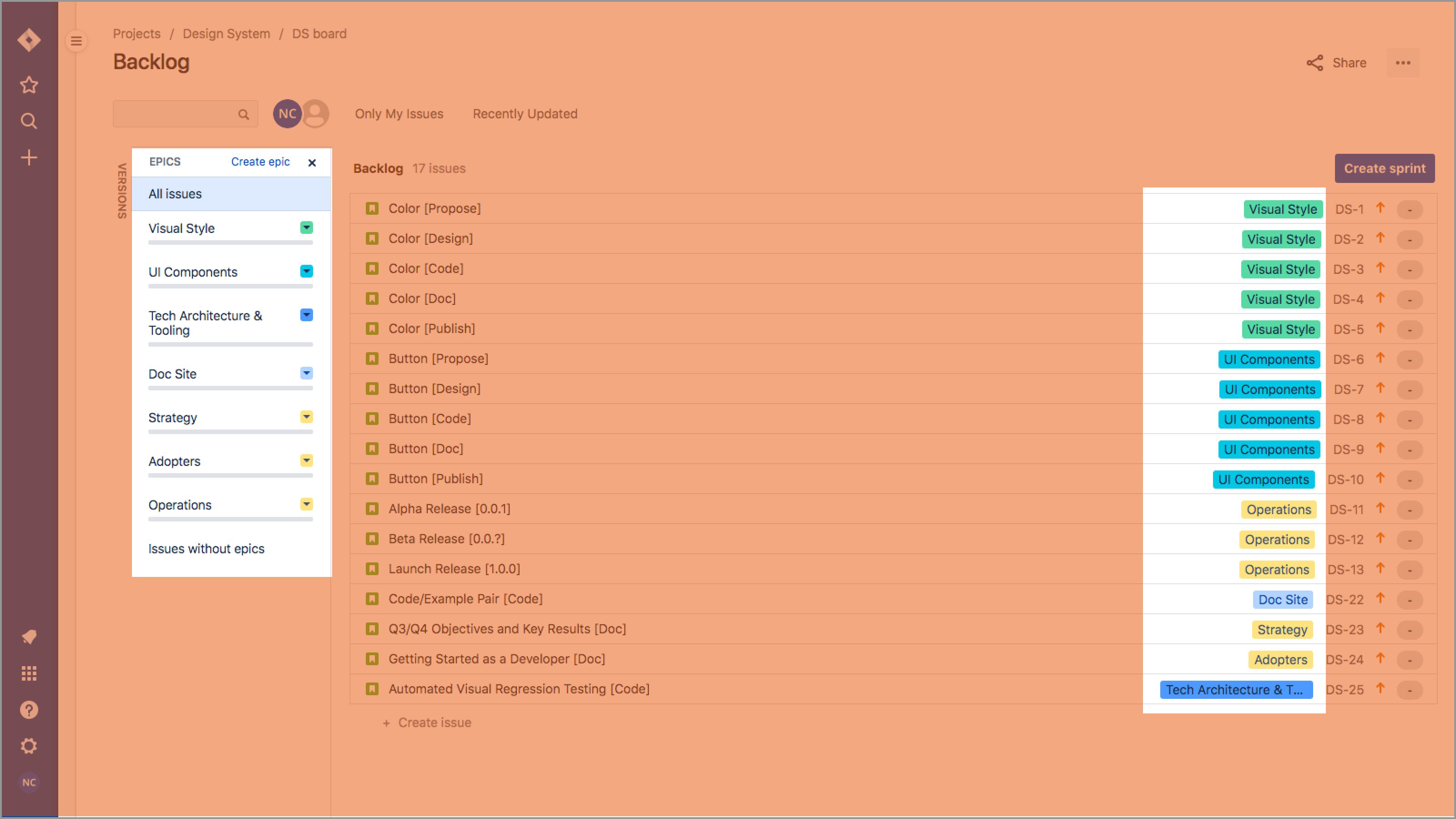

Epics organize work into well understood categories for filtering (using the Epics panel on the left) and scanning (a story’s category as badge per row). Too many epics can overwhelm. So we’ll limit epics to evergreen categories, formative epics for early work, and epics representing growth or change.

Some design systems work is like the mail: it never stops. These persistent categories represent the work we are always doing:

When starting a design system, big investments are required even if they eventually taper off into normal business as usual. As a result, a formative period may also deliver on epics like:

After a formative period yields a major release, work transitions into business-as-usual. Nevertheless, the system can evolve and grown with work like:

Versions can break down the work into periods that result in delivering value to your users. These versions enable teammates to see badges per backlog row and filter features and other stories relate to a particular release (such as 1.3.0) or period (such as 2020Q1).

Systems versioning at the library level may group stories into versions of:

Alpha (0.0.x) to validate a system’s design and code architecture, such as for color and typography applied to icons and buttons.Beta (0.x.0) to progressively deliver a stabilizing set of UI component design, code and documentation to early adopters.Launch (1.0.0) for a complete library’s first major release.Ongoing (1.x.x) for work out-of-scope for launch, yet not breaking.Next Major Release (2.0.0) to bucket those stories – small to large – that will be breaking changes or major shifts to save for later.Not Yet Prioritized for work that’s come in recently but hasn’t been assigned a release.Business as Usual for work that’s part of a day-to-day operations and not tied to any particular delivery.

Once such a team completes its Launch 1.0.0, versions can shift to:

Next Minor Release (1.4.0) for work to deliver in the next sprint or two, after which retire that version and add Next Minor Release (1.5.0).Ongoing (1.x.x) for work out-of-scope the next minor release.Next Major Release (2.0.0)If the team tends to deliver a minor release just about every sprint, then the Next Minor Release approach is redundant. Instead, the active sprint serves the purpose of scoping the next minor release, and all near term work organized into the Ongoing (1.x.x) version.

For teams versioning at the component level, we’ll use versions to group stories by an increment of time, such as:

2019Q4, 2020Q1, and 2020Q2 for three upcoming quarters.Not Yet Prioritized, Business as Usual, and other designations.Some teams use many, many more epics and may not even use versions. When I introduce the approach described above, their chief complaint is something like “These epics are too broad. There’s too many stories per epic to deliver something meaningful.”

However, epics shouldn’t stand alone. Instead, filtering by epic and version should result in a small set of stories pursued as a meaningful objectives. Both dimensions – independent, applied together – has proven incredibly valuable.

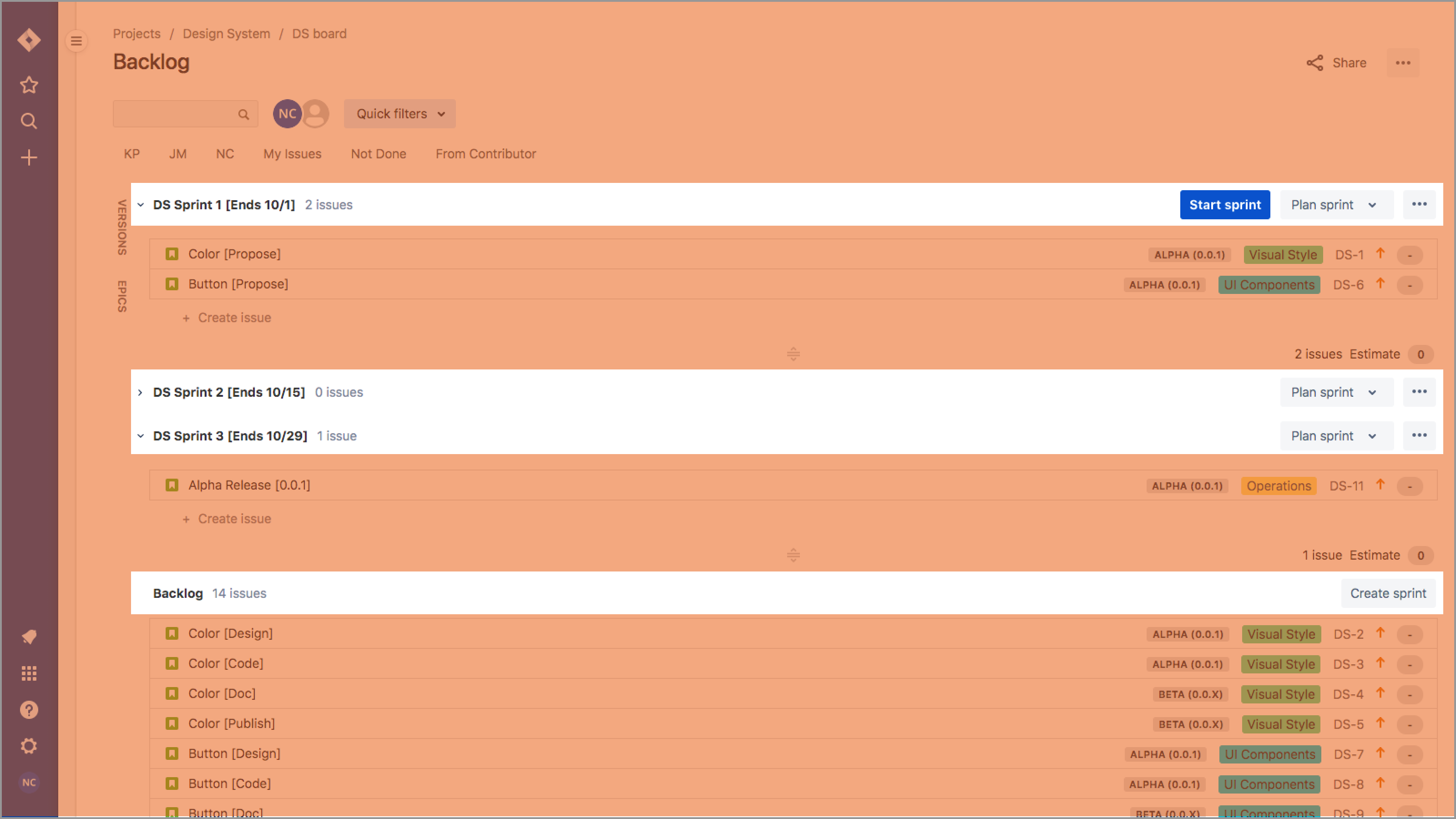

I’ll create Jira quickfilters to ease filtering stories by team members using succinct initials (such as NC for Nathan Curtis). These filters are essential during ceremonies like standup and planning as we discuss stories person by person. Recently, Jira has added an avatar-based list of assignees above this feature, also useful for filtering.

Beyond names, other quickfilters have proven helpful:

Most of my systems teams iterate in two-week sprints. My habits for managing sprints include:

Let’s be honest. It ain’t simple to make visual style and components at high quality to serve many contexts. There are so many tasks involved to setup, make, test, present, review, and commit work each step of the way: [Propose], [Design], [Code], [Doc], and [Publish]. I recently created a superset of all these subtasks, across steps, that many teams conduct.

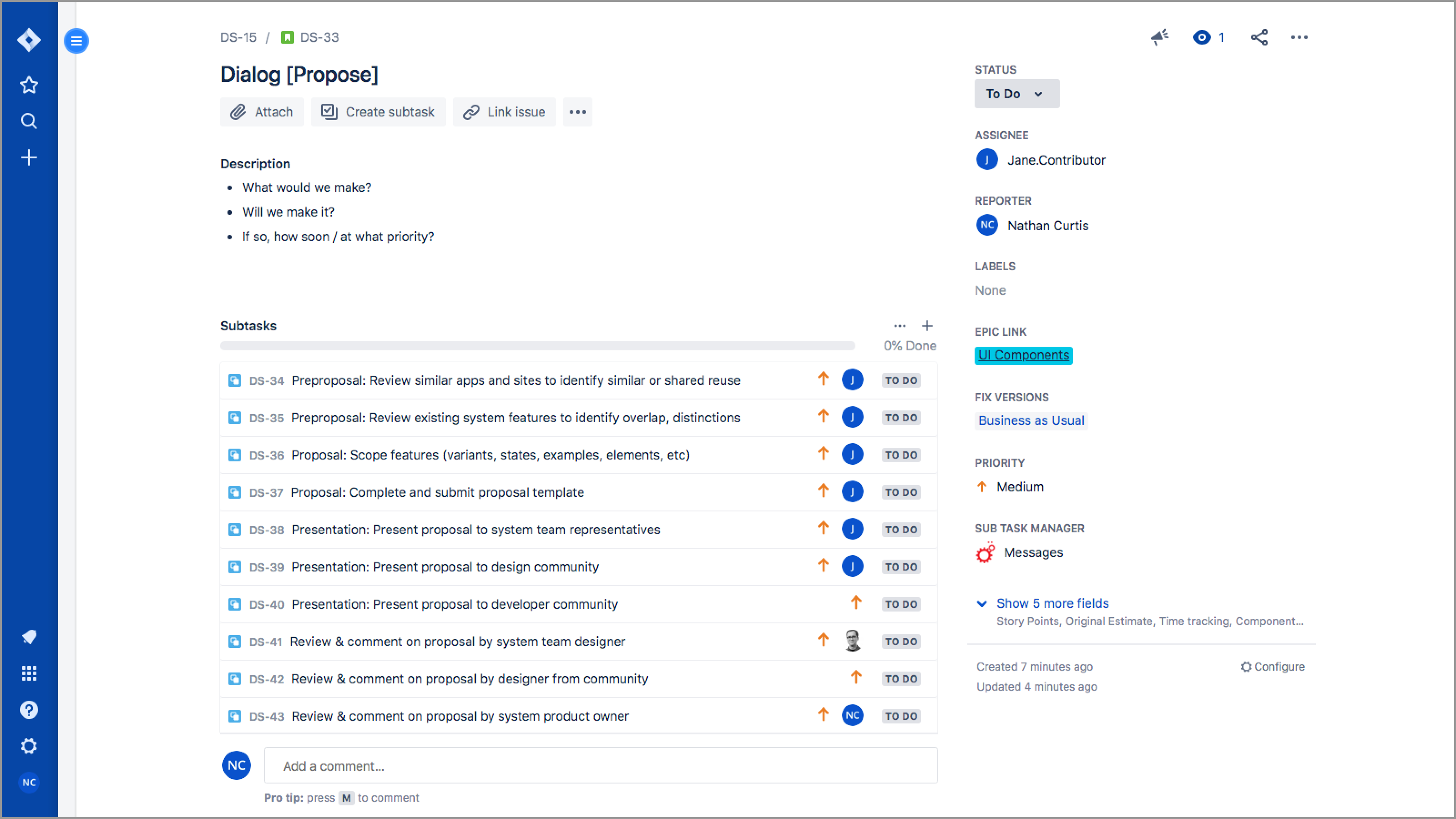

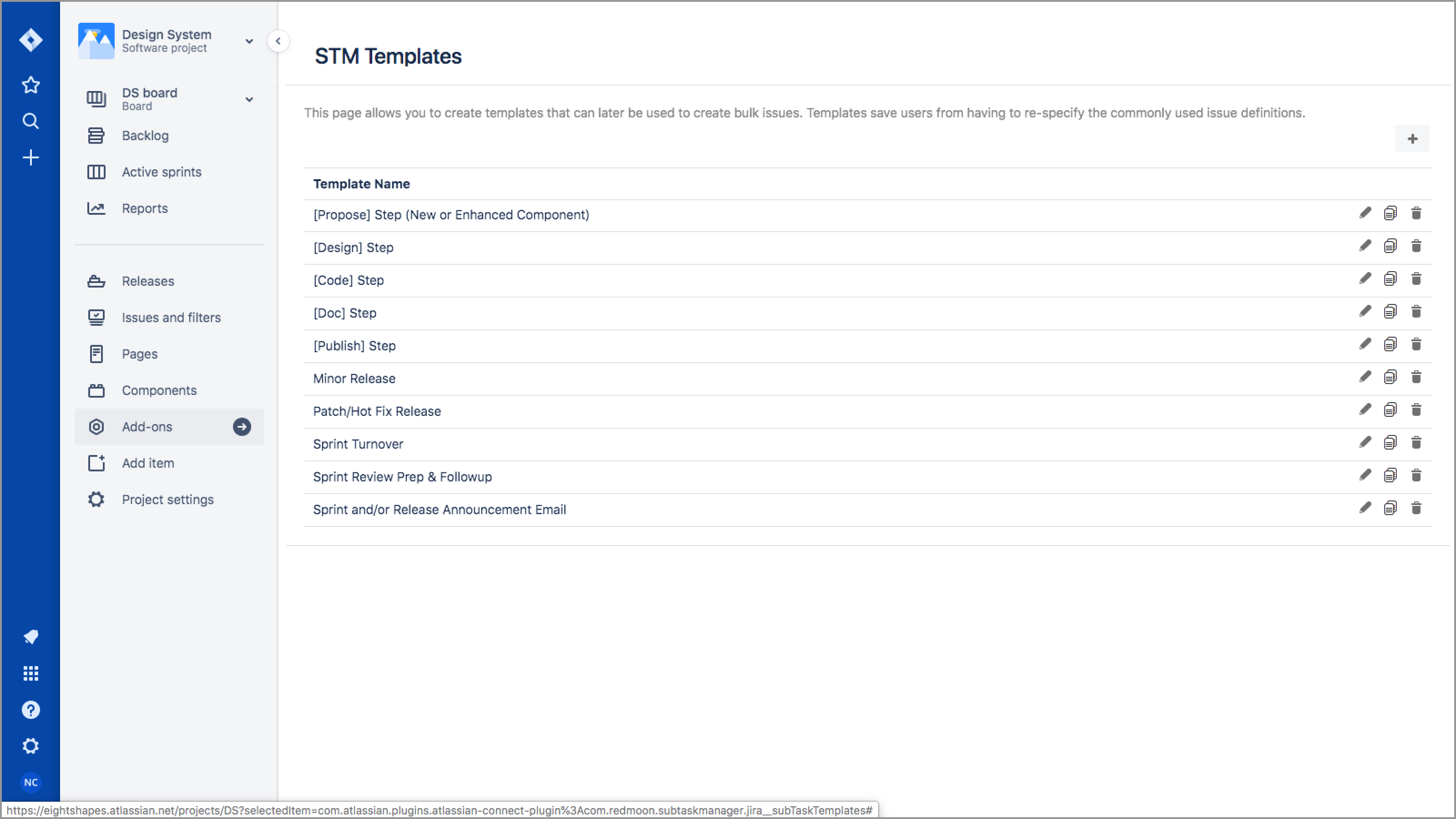

Yet, once you tame the beast of all these repetitive tasks, you can use a Jira add-on to create and apply subtask templates — a collection of reusable subtasks — to common story types. There are many add-ons to choose from, such as Automatic Subtasks Add-On and Subtask Manager (shown here).

![Subtask Manager Template of many [Proposal] step subtasks](/images/articles/using-jira-for-design-systems/8.png)

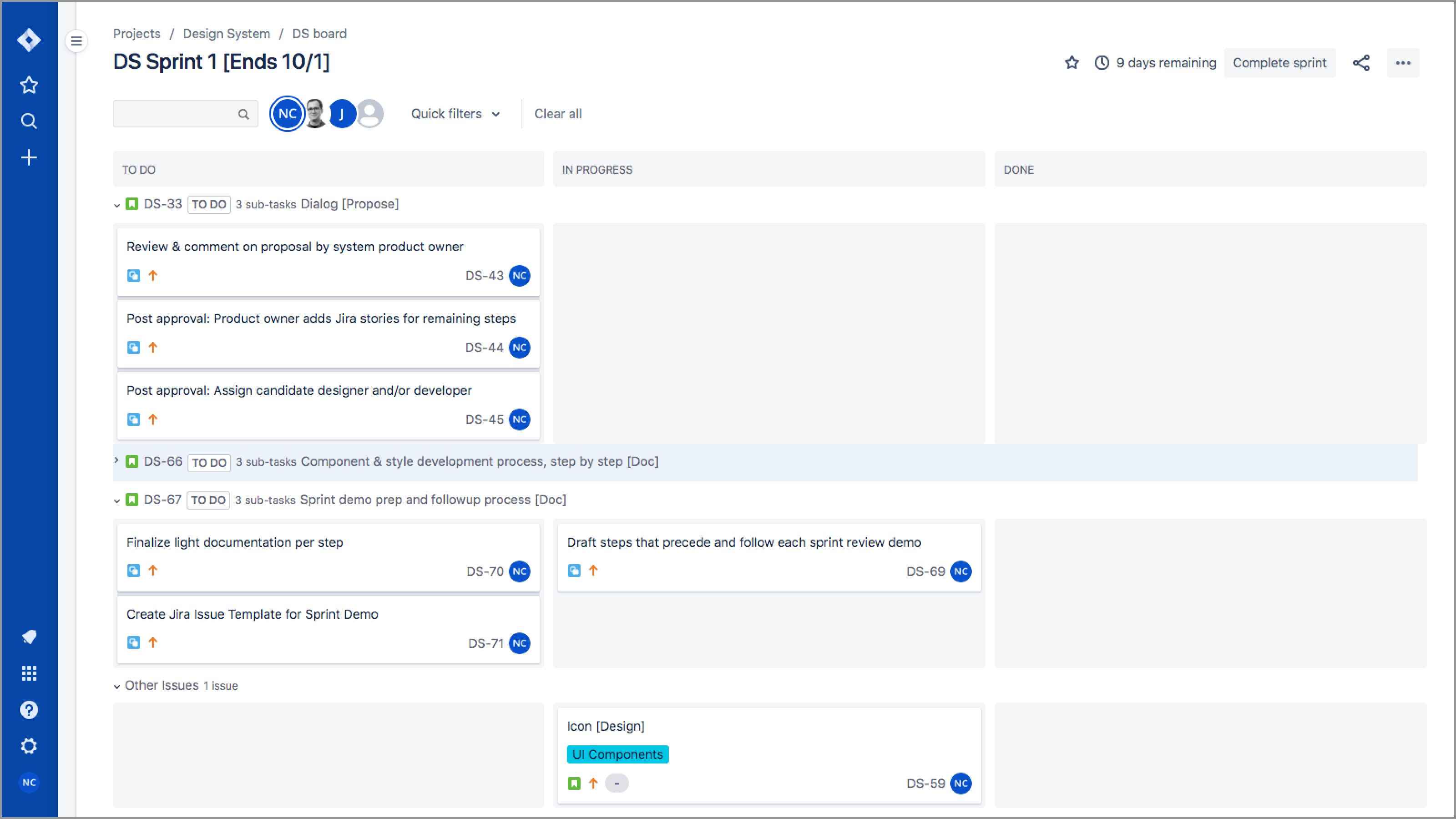

As a step begins, apply a template to auto-generate subtasks needed. For example, a [Propose] story could apply a subtask template with:

For a contribution of a new Dialog component, we’ll populate a [Propose] story with relevant subtasks, assign most of them to a contributor, and also assign review tasks to the team member shepherding the work.

Subtask templates are addictive. They’ll remove the mundane repetitiveness of typing in work, and provide immediate clarity and structure as a checklist. Within days of creating our first template, we’d created templates for:

[Propose], [Design], [Code], [Doc], and [Publish]) as well as specialized, shorter template for [Defect].Team norms around how to use subtasks effectively take time. Encourage patience as your team adapts. The detailed descriptions, assignment timing, and handing off work takes some getting used to. Over time, I’ve come to embrace behaviors like:

When used most effectively, Jira becomes a hub of communication and the central tool for facilitating regular team-wide ceremonies of grooming, planning, and standups.

Working with (most often a small subset of) the team, I’ll present Jira’s Backlog view to:

Not Yet Prioritized version.After the team agrees on sprint goals, we’ll focus on Jira’s Backlog view to:

Most teams I work with conduct a standup two- to three times per week, using Jira’s Active Sprints view simple columns of To Do, In Progress, and Done to chart and progress current tasks. During that meeting, I’ll:

I’ve seen some teams employ a much more complex Active Sprints view, with many many columns corresponding not just to top level tasks (like Design) but also reviews and handoffs (like PR Review). That has never worked for me, in that our tasks are to heterogeneous, our steps and subtasks too fluid, to make a top-level status board that rigid.

Jira is an acquired taste, and using it effectively across a team takes time, commitment, flexibility, and a willingness to converge on a shared language. In my work across many teams, Jira’s effectiveness seems correlated with those teams invested in a system’s long arc. Those are just the teams and systems I want to work with most.

EightShapes can energize your efforts to coach, workshop, assess or partner with you to design, code, document and manage a system.