Operating a design system shares much in common with operating any product venture, from developing to supporting to marketing it. With marketing comes communications, spreading messages far and wide to engage designers and developers how they want to be engaged. Addressing their problems. Using the tools and places they observe and participate in.

Marketing communications tools aren’t new. Yet, for design systems, those tools help us structure our heretofore loose thinking. Zooming out, a design system can review target audiences, channels, and messages, compose a strategy using message matrices, and envision campaigns to launch a major release or manage change. This story – and workshop activity ideas & templates it includes – offers a look at how to put those pieces together.

Communications matter. In countless conversations over the years, system adopters and contributors invariably declare a system must be:

To achieve all those qualities, a design system must communicate well. If a system communicates poorly or — even more commonly — not at all, it’s transparency, inclusiveness, and trustworthiness suffer.

While most will instinctually dive into solutions (Send an email! Crank out a Slack message! Open a Confluence thread!), teams benefit greatly from backing up a step. Stop, for just a moment. Not every challenge is resolved by reflexively reacting with “Slack it!” Instead, let’s take a moment to consider outcomes.

For every communication you work so hard on: What actions, effects, or behaviors are you trying to trigger? What does change look like? How do you want this to turn out? What do you want to happen?

For design systems, outcomes that matter include:

There’s surely plenty more outcomes than those above. These outcomes also directly suggest opportunities for measurement — even of sentiments — that help us understand if our design system is successful.

Given those outcomes, how can we plan our communications more deliberately? All strategies require us to think about who we communicate to (target audiences), where we communicate to them (channels), and what we’re trying to say (messages).

The primary target audiences of system comms are designers and developers. These staff members are on the front line using system tools (like Sketch and code) that weave system features (like visual style and UI components) into the digital interfaces they build every day.

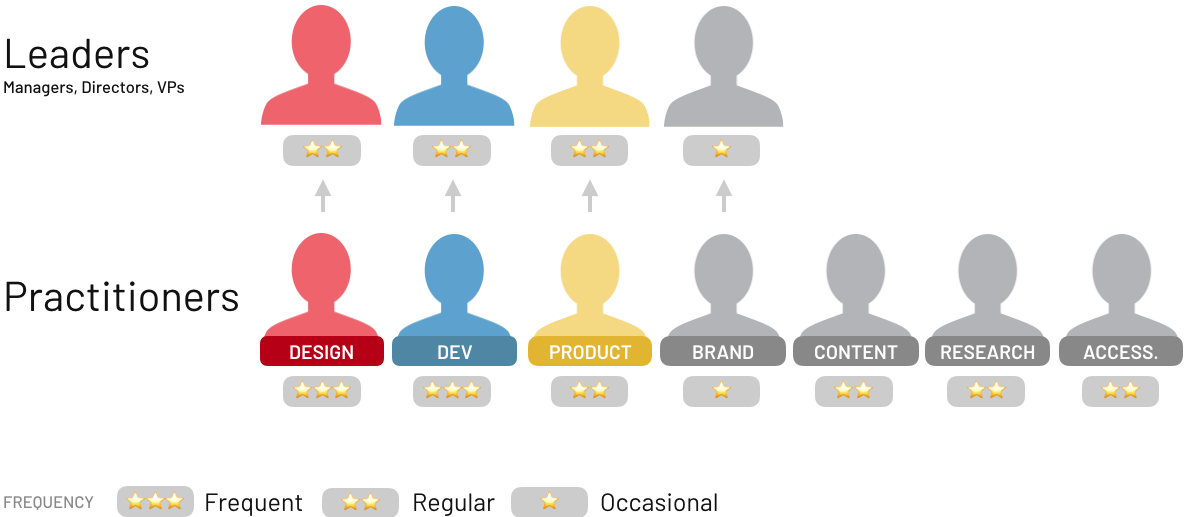

Nevertheless, a design system program communicates to a broader array of individuals at varying frequencies, including:

Takeaway: Communications is hard because there are so many different types of people with different needs, vocabularies, and levels of system awareness. They all see the same world differently. Therefore, your messages must be tailored to how they learn and interact in channels — including face-to-face discussions or slide presentations — that they are comfortable with.

You’ll need to know where each audience is to get the messages that you’ll have for them. In communication, this is all about leveraging channels: any way, path, or place where a target audience can pickup a message. In design systems, there’s a wide variety to choose from.

A messaging app such as Slack or MS Teams is essential for any program.

Many system teams set up communications by target audience, such as:

#system-design: Help, sharing ideas, cross-product visibility, naming things, meeting minutes of critique meetings#system-development: Help, calls for API/PR reviews, naming things, announcing/summarizing working sessions#system-general: Catch-all for other communications, major announcements, sprint reviews, calls for participation in planningTeams may eventually expand to other channels for specific purposes, like :

#system-help (for focused, threaded conversations)#system-[ambassadors] (for a semi-private group, such as key advocates)#system-ux-patterns (for narrowing discussion to a special interest)Email, Twitter, text messaging, and even alerts embedded in system tools like a Sketch plugin or command line warning of a detected deprecated feature.

More permanent content may be authored and published in a variety of channels, such as:

Routine meetings where system team members present or participate are opportunities to communicate. These can include sprint reviews, critiques, technical working groups, readouts to program sponsors, and special interest groups (like UX Patterns).

In contrast to the ideal routine a system achieves, there’s also messages that require more deliberate preparation, authoring, review, and polish. These include demos of major releases, tech talks, brown bags, and training curriculum. Usually, slide presentations are the output, and teams are amazed at just how much time this soaks up across team members to do well.

My favorite communication channel ever? Easy. One software company preferred analog (Kanban walls of Post-Its, whiteboards, etc) over digital (Jira, emails, etc) communication. Therefore, the system team borrowed a channel used by other groups: bathroom stall doors to post newsletters to captive audiences. That’s innovating. I love it! What fits your culture?

Design system teams are often surprised and overwhelmed by the diverse array of messages they communicate to different audiences through different channels.

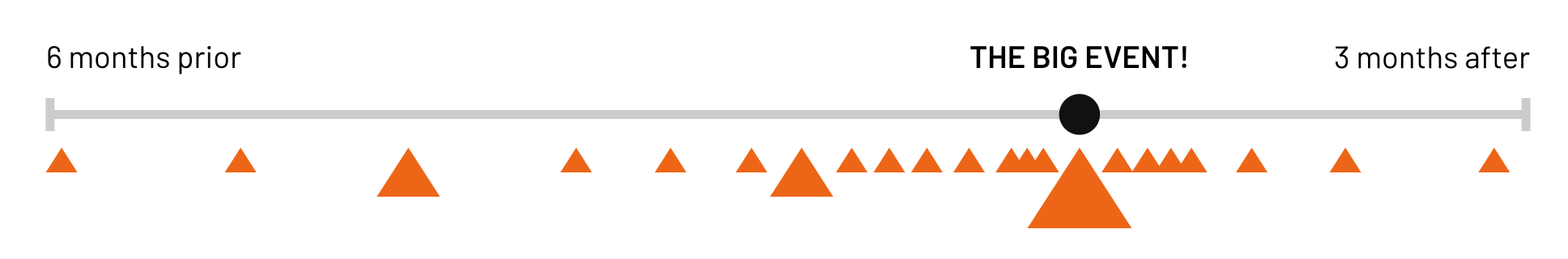

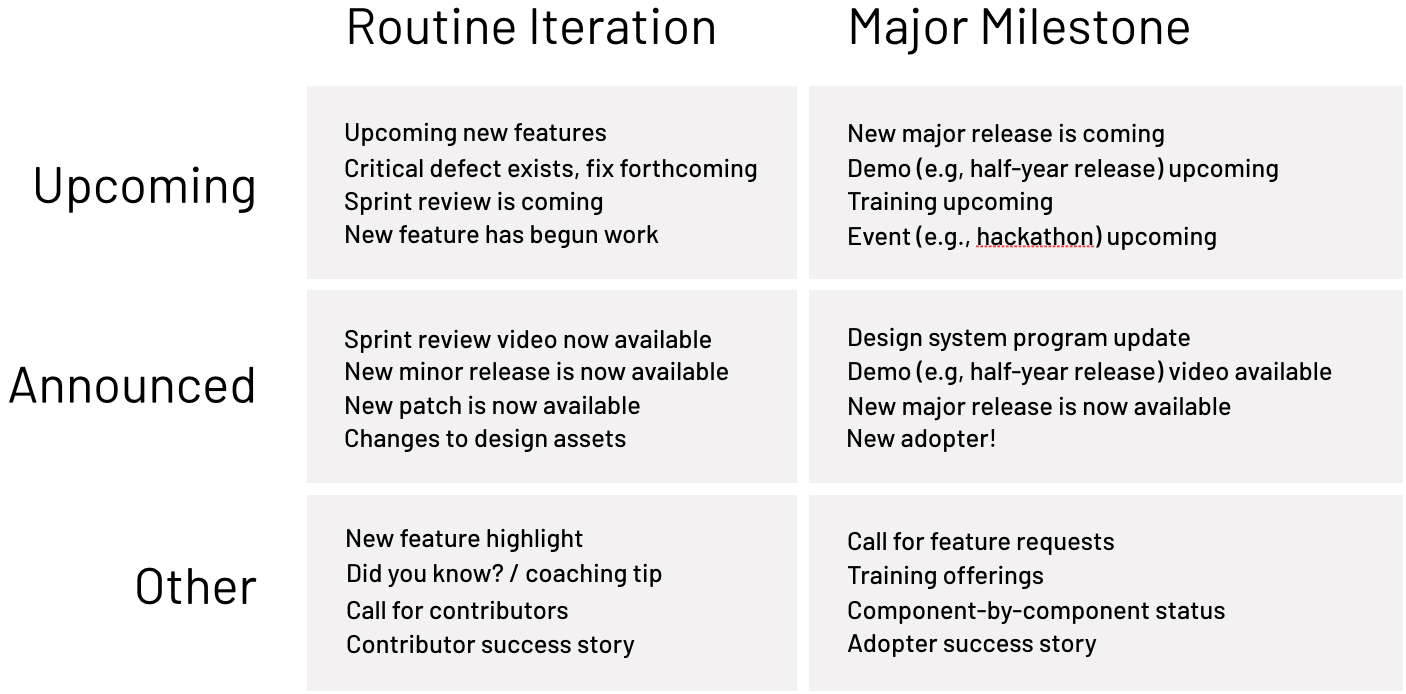

A fairly quick whiteboard exercise can reveal the copious, seemingly random array of message opportunities. That said, I’ve found structure in this list by organizing around two dimensions: timing & regularity.

There’s a duality in many messages, from minor releases and and patch fixes to sprint reviews and training sessions: it’s either upcoming (sooner or later) or it’s announcing something that’s already happened. Therefore, when planning some messages – particularly routine ones – we’ll be sure to consider hitting on both sides of an event.

Messages also seem to be either regular or irregular. Most teams develop a rhythm of workflows they repeat over and over: sprints, releases, patches, asset updates. For example, a routine message could be the announcement of a new minor release, targeting all system customers in the #system-general messaging channel and other locations, using a template like:

*NEW RELEASE*

[system name] *v#.#.#* is now available, including:

* *NEW* [Feature name], including [feature details]

* *NEW* [Feature name], including [feature details]

* [Feature name] now includes [feature details]

* [Feature name] [feature details]

* Fixes that include [fix], [fix], and [fix]

Read release details at: [Release history URL]

On the other hand, other messages are associated with a major milestone of the program, often requiring uniquely crafted, customized messages that require more effort. Major system milestones emerge during the life cycles of the features and technologies you use, including:

Such a major event requires a campaign of communications as the design system announces, approaches, launches, and follows-up this event.

Once your team has identified a range of a messages, it can be helpful to organize those messages across those two dimensions to look for patterns, efficiencies, and priorities. This bucketing will also yield opportunities for messages that aren’t timed around an event, such as:

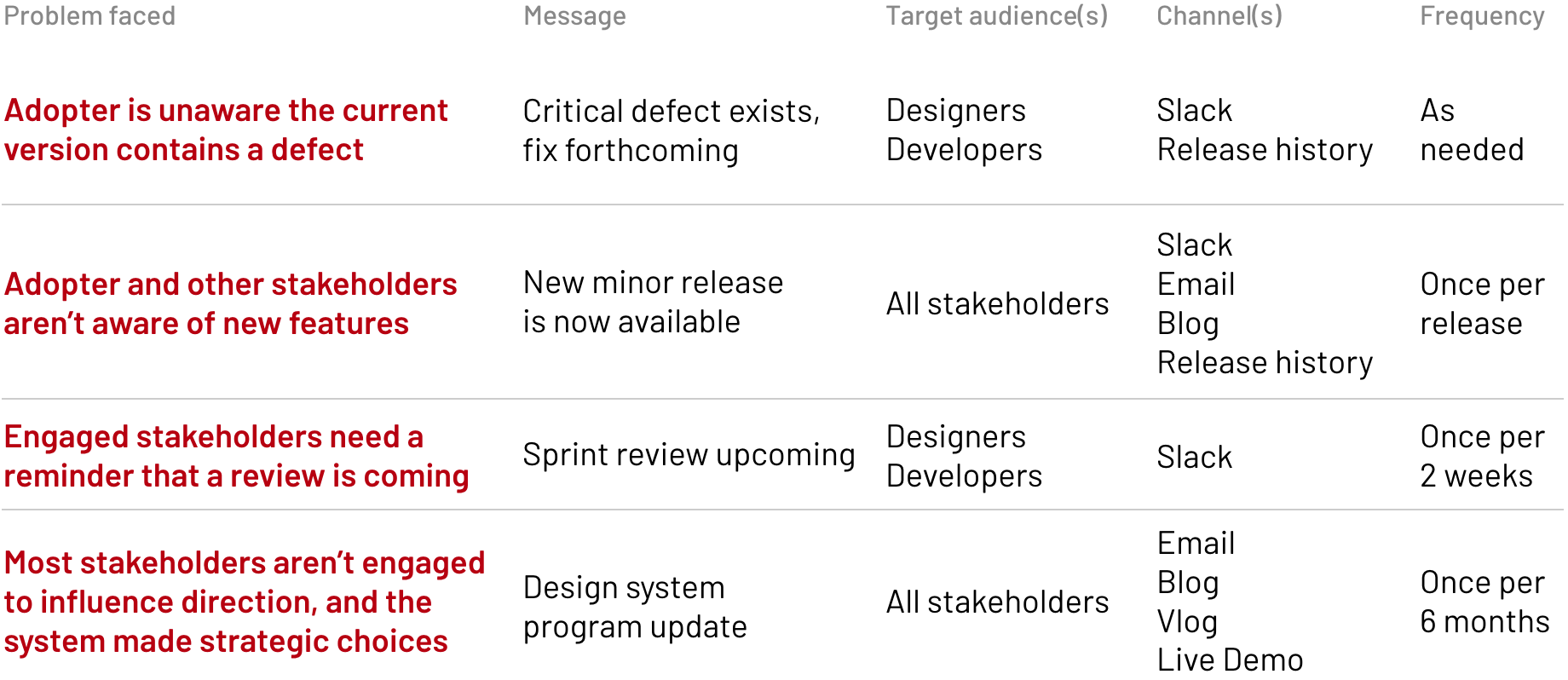

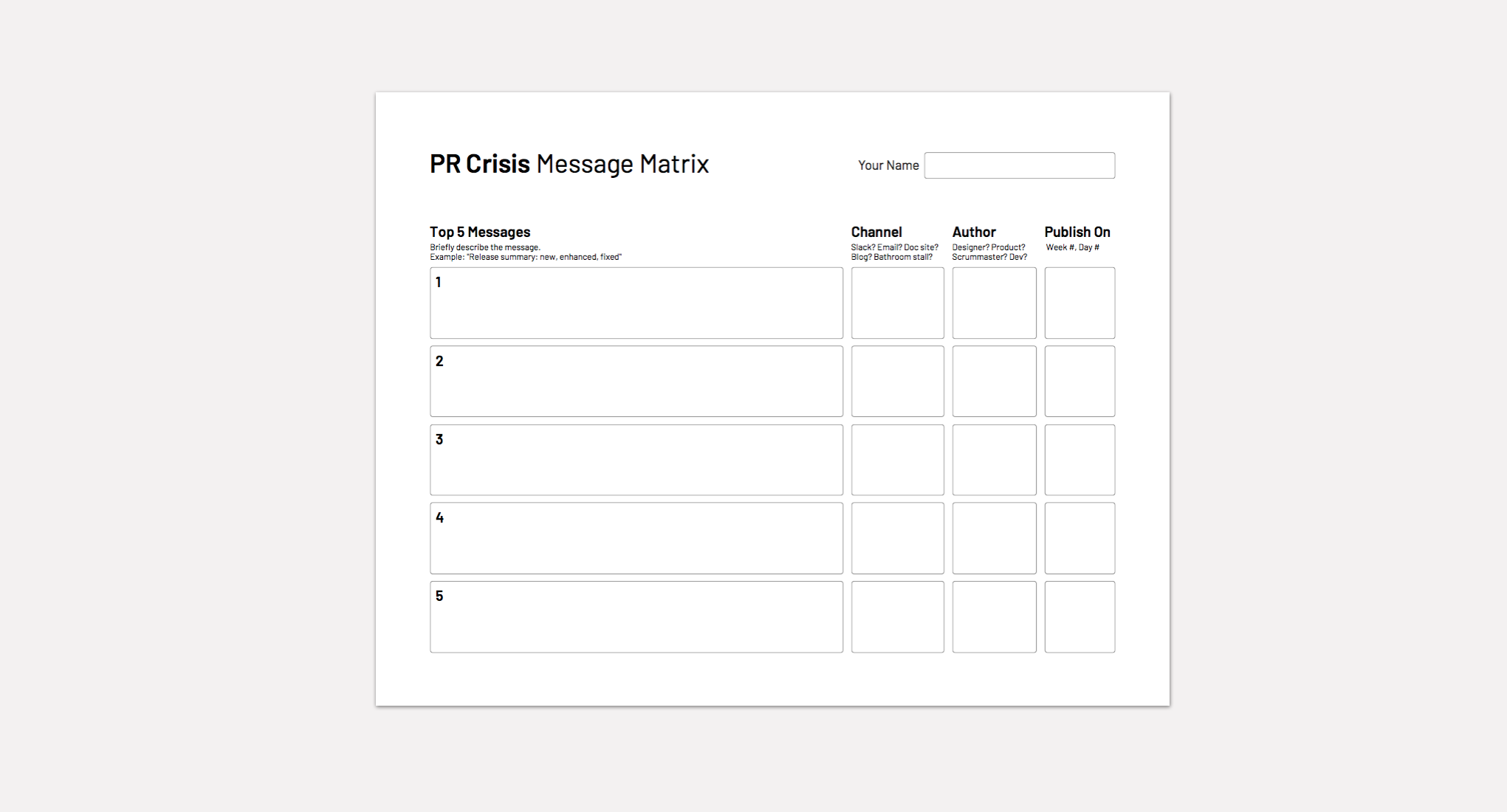

A message matrix brings these components together to form messages that address problems your adopters and contributors may face. A message matrix is a table of messages, itemizing each high-level message with associated problem statement(s), channel(s), target audience(s) and frequency by which it’s communicated.

For example, if a design system discovers a critical defect that impacts everyone, adopters need to know, FAST! A messaging tool like Slack is the proper channel to get out the words of warning to everyone, and then Slack, a release history, and other channels should be used to spread the word that the fix is available.

A message matrix enables those not steeped in marketing communications lore to plan messages with structure. The matrix isn’t meant to be formally maintained over time. Instead, the matrix aids individuals and teams planning together and helps authors identify tasks to compose and distribute messages over time.

Takeaway: Challenge your systems team to relate the messages they project to the problems their constituents face. By constructing a message matrix, you can prioritize and reorient investments towards messages that matter. Additionally, this structure is useful when overlaying communications thinking onto something as big as planning a major release cycle or as narrow as discussing how to handle a critical defect.

Recall that every message needs a purpose, driving receivers to a desirable outcome. Some messages carry a more passive intent of informing and educating. Others intend to drive receivers towards overt action, such as:

Takeaway: To be sure, design systems can’t be all up in your face all the time. However, a design system must make the right thing to do the simple thing to do. Therefore, ensure that communications drive customers to act, flowing them into workflows and behaviors that matter to them.

Oh my goodness, all the messages, all the channels, all the people, all the monotonous workflow drudgery! Can’t I just get back to Sketch or my code editor? No doubt, designers and developers pursue careers to design and develop things, not become marketing specialists. So who’s gonna do all this writing, reviewing, publishing, and monitoring? Turns out, different teams approach this in different ways.

Some teams can be passionate about everyone capable of doing everything, spreading out the love of communication across all team members.

Pros: This model leads to a shared team understanding and awareness of issues, connects individuals in thinner slices to design and dev communities, and cultivates individual communications skills.

Cons: Management is a headache, tossing communications around like hot potatoes every time an opportunity arises. Who’s doing it this time? Who’s reviewing it? Oh the tedious lack of clarity and resolving with each go around. Plus, message consistency takes a hit.

Other teams concentrate communication efforts into specific team members, often product and project managers combined with design and development practitioners with stronger communication skills (often, leaders).

Pros: Easier to predictively manage, and messages are more consistent.

Cons: Those communicating can get a bit more burned out, and those “not communicating” (at least formally through these means) feel left out. Plus, if it’s the leaders crafting all the messages, that may disconnect them more from participating in how features get made.

Takeaway: Deciding who communicates what puts team values in conflict: consistency vs inclusiveness. Management clarity vs skill development. Discuss these competing forces as a group, and do your best to create opportunities for those who want a voice.

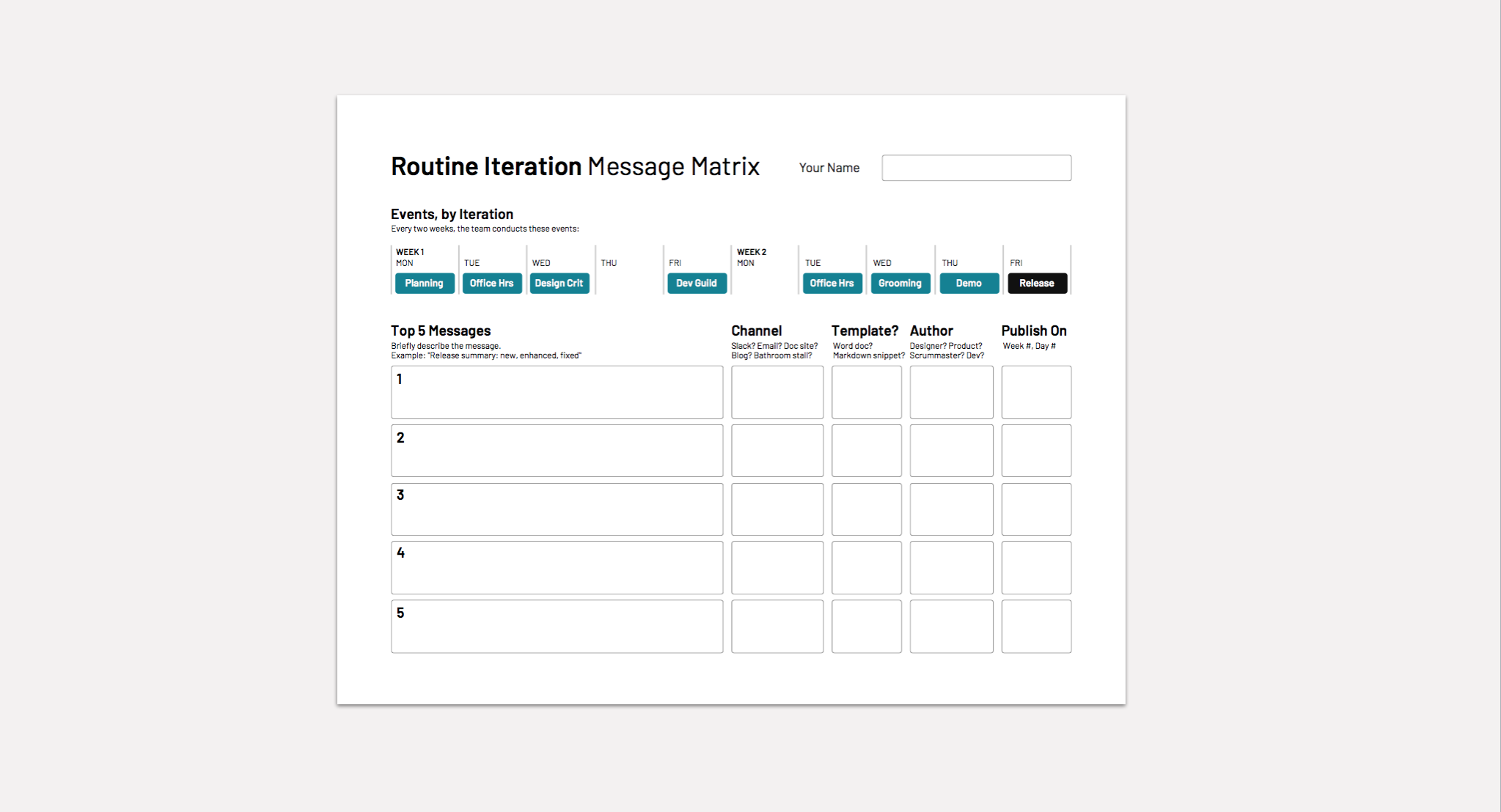

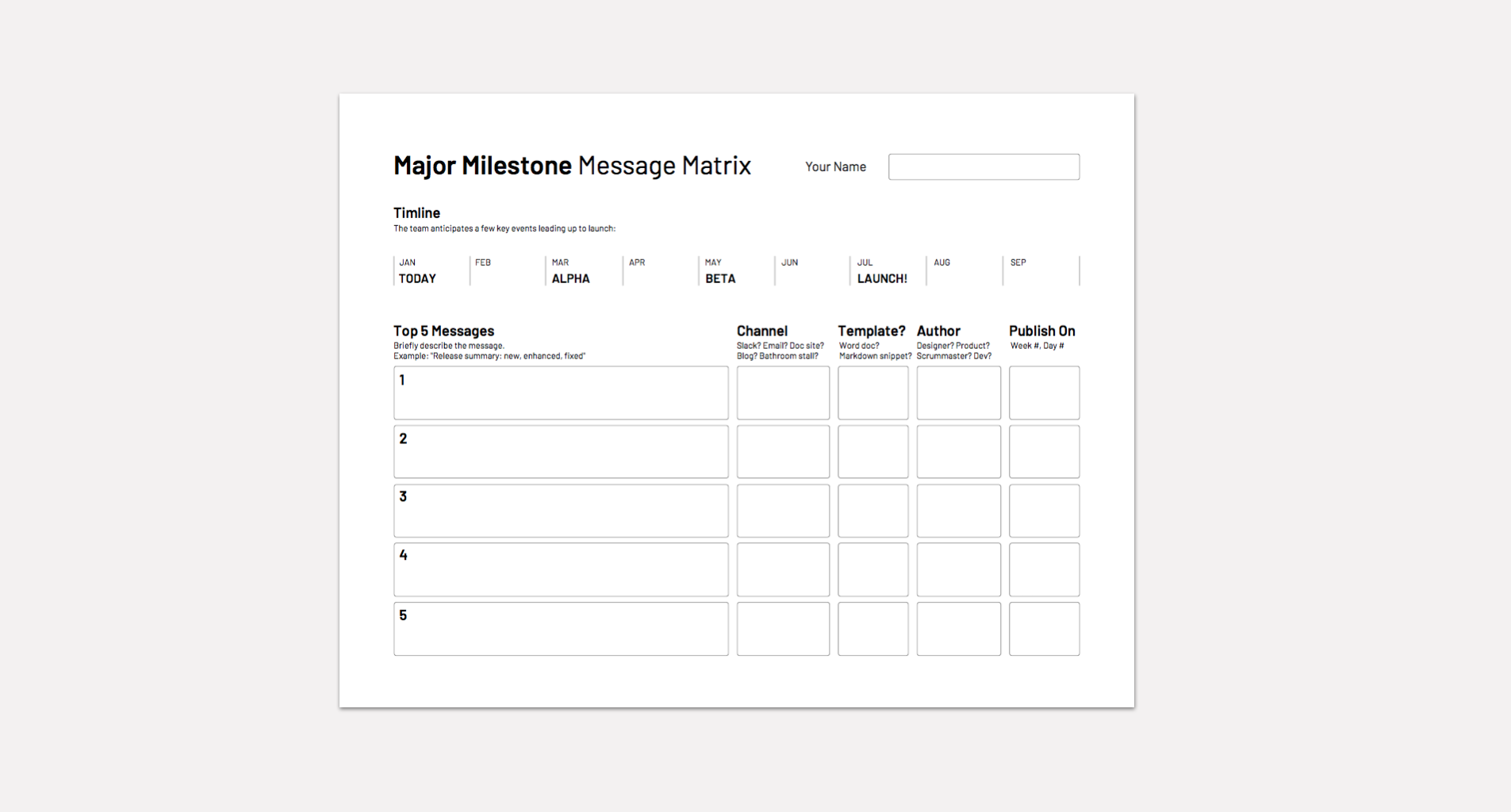

To help design system programs zoom out and plan communications, I’ve crafted a few message matrix templates centered on different scenarios. I could imagine this activity being particularly relevant for a three-, six- or twelve-month planning session conducted by the design system program.

The format organizes tables of four to six work as a group to complete a matrix, and then share results with other tables. Iteration spans rounds, such as starting with Routine Iteration, iterating that matrix if necessary, then letting the table brainstorm on a major milestone or PR crisis.

Not every system team runs a predictable cadence of two week sprints each that result in demos and, usually, minor releases (although some that I work with do). That said, every system has some kind of cadence to plan, work, critique, demo, and release things. How might an interval-based message matrix get your team thinking about:

It’s common for a design system program to be prepping for the next big thing: a switch to web components, ditching Sketch for Figma, whatever the hot topic might be. Shift the team’s mindset to that of a marketing campaign: a planned collection of messages spanning the effort before, during and after the rollout.

It happens. The design system team solicits input, charts a course, and begins the work. And then the mutterings happen. For example, a subgroup of developers representing a couple flagship products don’t like the technical direction. Rumors abound. Whispers even hint at forking the system!

Avoid public relations crises like these. Yet, if they happen, be deliberate about communications. Over even a two or four week period, how might a message matrix help you…

EightShapes can energize your efforts to coach, workshop, assess or partner with you to design, code, document and manage a system.