Every system team I’ve worked with yearns for a better — even perfect — contribution workflow model. Nobody feels they have it (although some have parts of one). They all seem to tell their design and dev constituencies continually that “We’re going to refine our contribution model next quarter.”

Trouble is, the premise of a perfect model conflicts with a harsh reality: teams must optimize multiple contribution models. Adding yet another icon is different from making a data visualization color hierarchy. Contributing a chip is simpler than contributing a functioning, high-quality data grid that’s like Excel in a browser. Making and fixing small things is different than making large, new things. Some things are contributed once, while others are contributed over and over and over.

Instead of addressing this diversity, teams force the contribution model towards a vague, catch-all workflow that’s ineffectively nonspecific. To succeed, we must first define contributions concretely, and then acknowledge that one-size-doesn’t-fit-all. This will lead us to different workflows for different scenarios.

Trouble starts with the basics: people don’t agree on contribution means.

Contributions taking tangible form are obvious. Completing an annotated component design as “ready to code” is a contribution. Merging a code fix for a defect is a contribution. Authoring and publishing a Do/Don’t guideline is a contribution. All are measurable, tangible change to move a system forward.

Yet, so many people frame softer activities as contributions too. Is offering verbal feedback during a design critique a “contribution?” Is influencing technical architecture a “contribution?” Is attending a meeting and nodding tacit agreement a “contribution?”

These soft, unmeasurable examples are important. They lead to tangible change. However, they muddle conversations of contribution. I distinguish untraceable collaborative acts as participation, not contribution.

Takeaway: Avoid characterizing any type of participation in a design system program as a “contribution.” Distinguishing participation from contribution will be hard, and it may risk those heavily participating feeling a bit left out. If you choose to cast your contribution definition wide, prepare for your model, its documentation, and conversation about it to cover a seemingly infinite array of system interactions.

So, if contributions aren’t an infinite array of different interactions with a design system program, then what exactly are they? I’ve had success in recent interviews with system leaders and adopting designers and developers setting a conversation’s context concretely with:

Let’s break that down line by line, shall we?

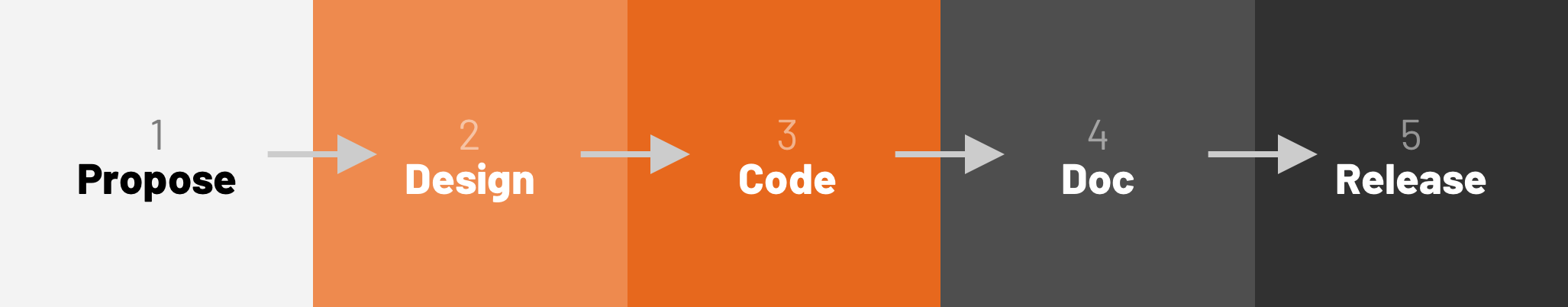

First, a contribution is a measurable completion of a step in a process used to deliver a system output. Different teams have different processes. What’s important is that a contribution is assignable with a concrete definition-of-done that gets a feature at least part of the way there.

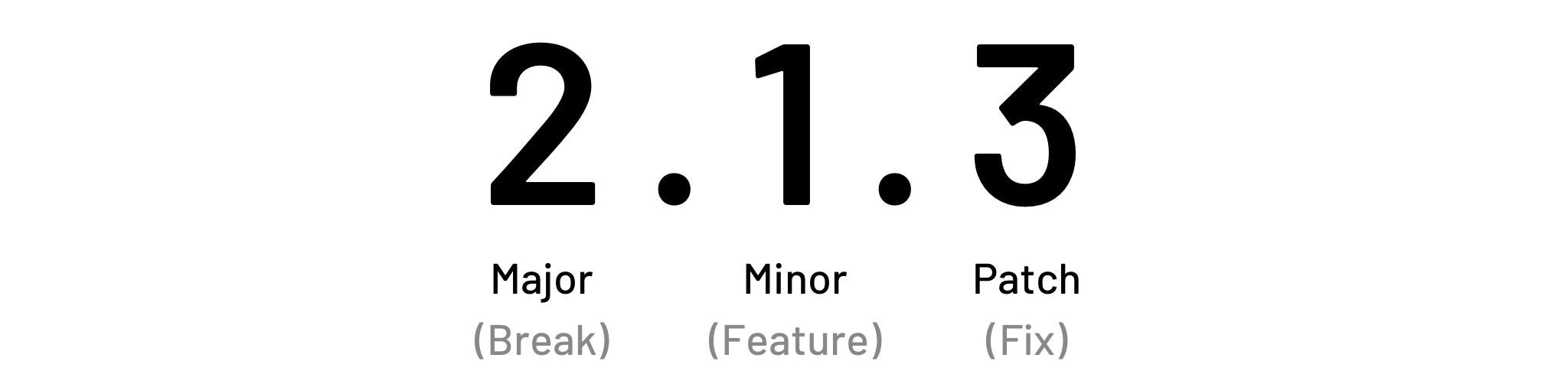

Second, a contribution has an impact commensurate with the scale of work involved. Terminology of new, enhancement and fix echoes semantic versioning. However, the takeaway here is that a contribution is a change that exists on a scale. More on that later.

Third, the contributor must be outside a core team maintaining a system as primary responsibility of their job. This relationship invokes the concept of federated contributions coming from a wide community.

Lastly, a contribution must be released through the system as available to the broader adopting community. Systems invest in documenting change through release histories, a sprint‘s email update, and other artifacts. Contributions as a subset of all delivered features suggests how to track, highlight and celebrate the work.

Takeaway: Be concrete in defining what does and does not constitute a contribution: What’s produced? Who produces it? How big is it? Where does it go so other people can get it? With those well understood, workflowS for jobs that need to get done come into view.

In interviews, I’d ask “So, can you describe types of contributions?”

Most respondents verbalize what amounts to a scale commensurate with size and complexity. They begin with the small: “Well, there’s lots of fixes...” They quickly pivot to “…and the new UI components too, of course...” Between the two is a muddled middle like “…and changes that evolve stuff over time.”

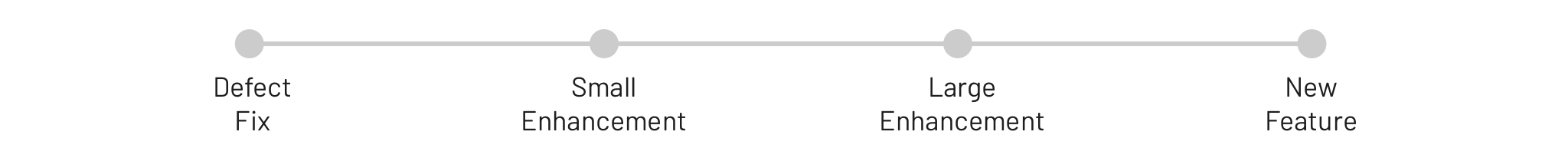

We can be more definitive: contributions exist on a scale from small to large, and we can identify meaningful points along that scale:

A fix of a defect. While mostly relevant to code (like an IE11 bug), this also extends to an erroneous Sketch library symbol label or doc site’s guideline.

A small enhancement where an architecture otherwise remains stable, such as adding an alert color (orange for “new”) to an existing set (red for “error,” green for “success,” and so on).

A large enhancement extends an existing feature, such as an alert’s dismissibility, description, and position (inline, block, or viewport-locked).

A new feature is self evident, such as adding a new alert component.

Don’t expect contributors to easily distinguish large and small enhancements. That’s OK. Conversations and scoping will eventually reveal how that nuance manifests in the depth of work and collaboration that awaits.

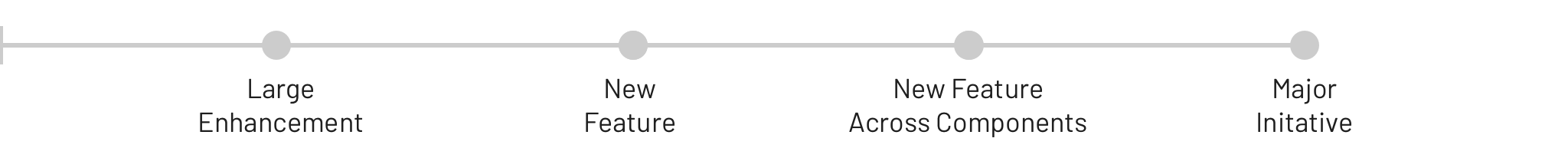

There are even bigger things, too. Systems undertake broader changes like a new feature (like Size) spread across an entire component catalog or a major initiative to switch from vanilla HTML/CSS to React or Web Components. However, work at that scale is never pursued as an independent contribution, and instead is coordinated and pursued by a central team.

Takeaway: Contributions vary significantly in size and complexity. To get it right, a contribution model must flex and decompose scope, steps and assignments into repeatable workflows of varying sizes and shapes.

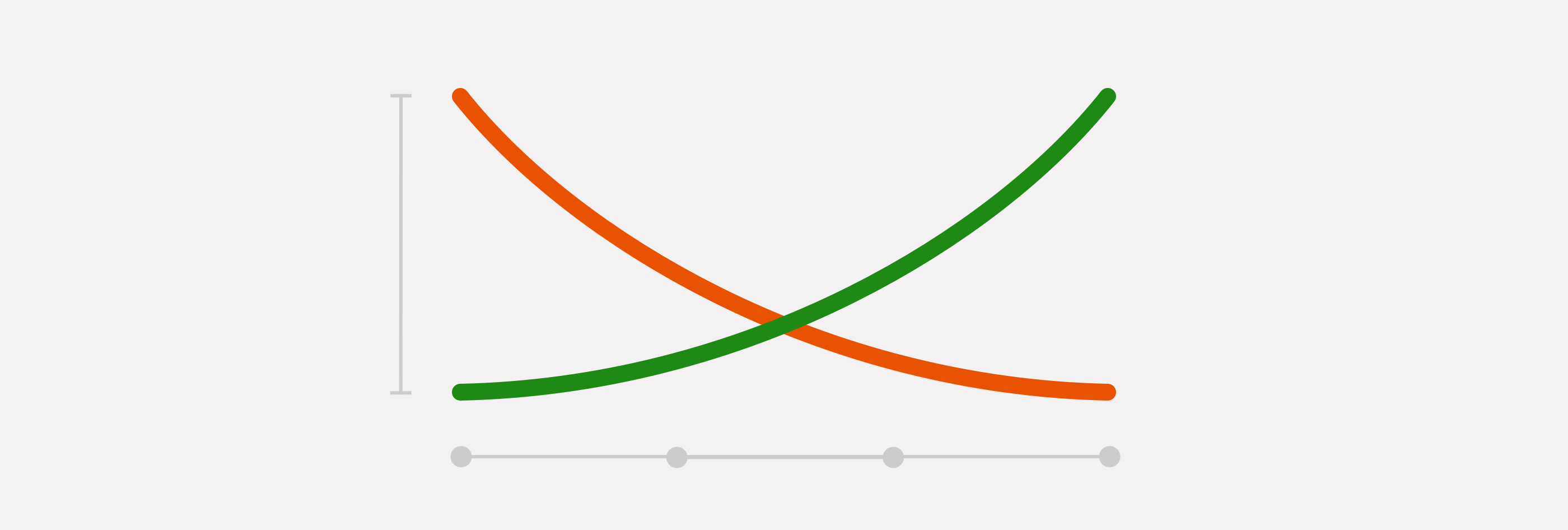

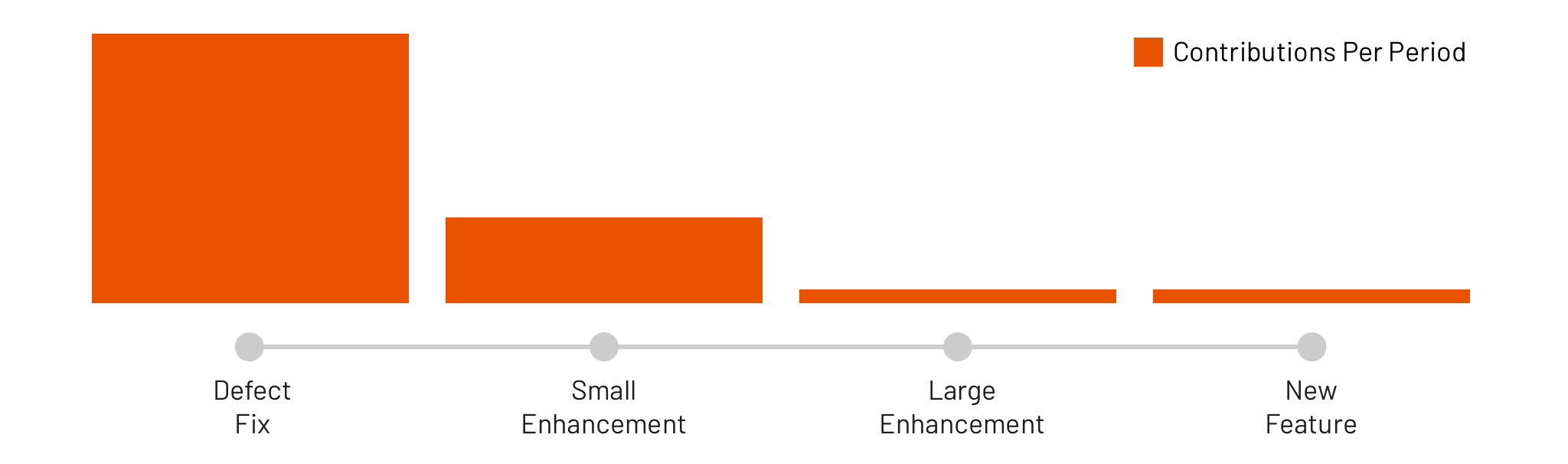

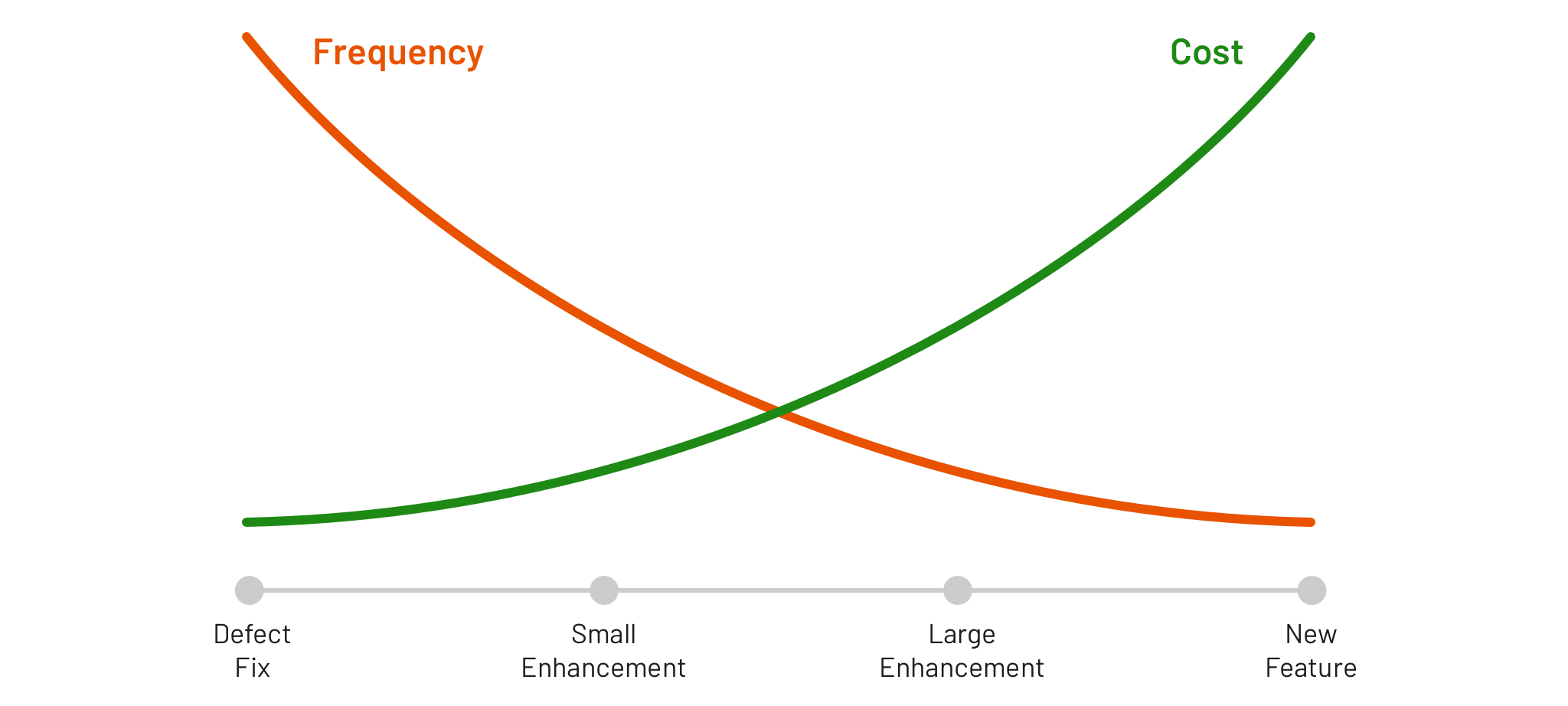

Once contributions are scaled, we can have more meaningful discussions around how frequently we can expect each to occur and how much each costs to those outside and inside a system core team.

All design system leads I talk to express that, if any contributor activity exists, a design system receives far more defect fixes and some small enhancements. On the other hand, large enhancements and new features are rarer, and that for those a contributor’s work requires and overlaps with partner(s) on the core team to get the work done.

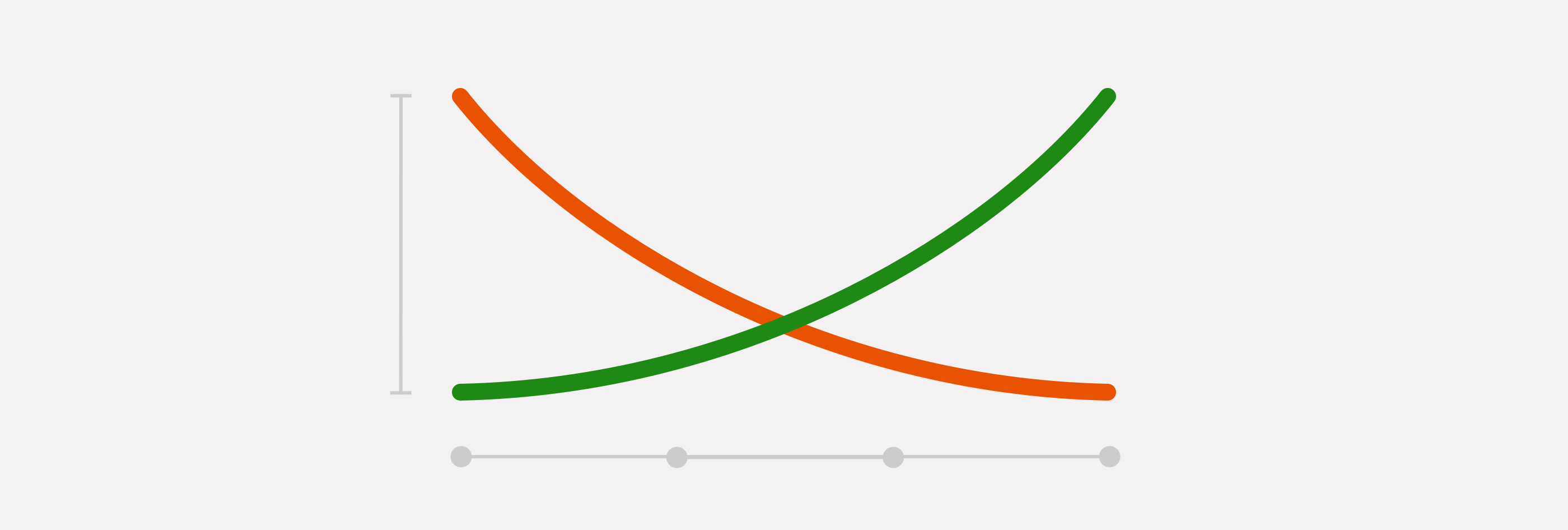

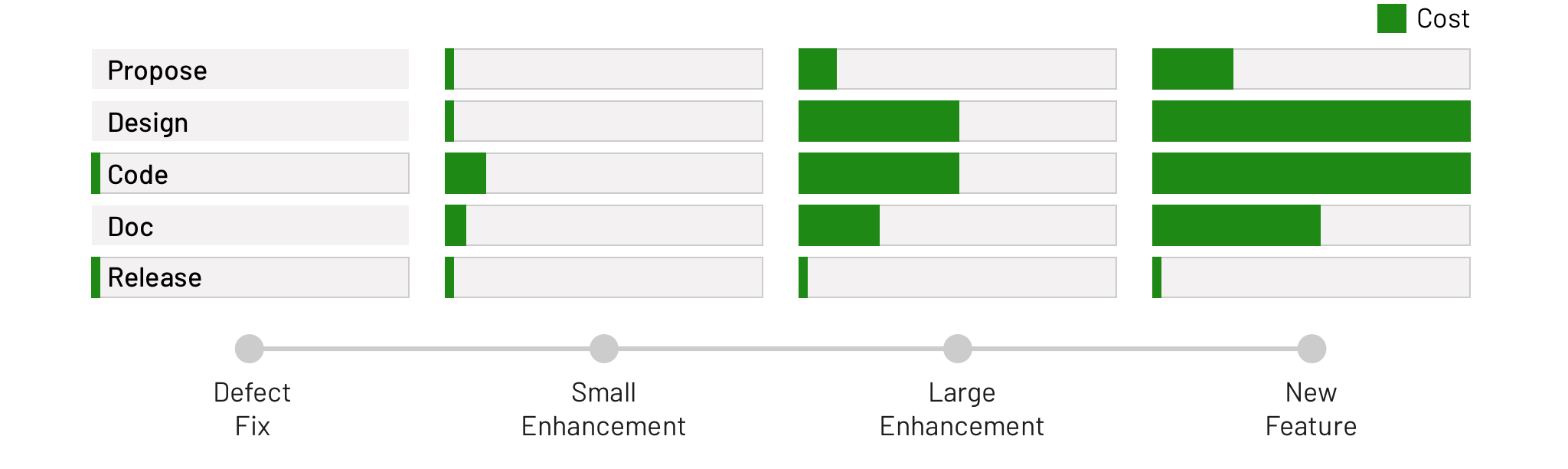

A contribution’s cost, as measured only by contributor effort, increases by type as well. While the contribution steps involved vary by design system team, the following chart visualizes the cost per step as defined by Design System Features Step-by-Step: propose, design, code, doc, and release.

For fixes and many small enhancements, the work can be more code-centric, completed and released by a contributing developer with little system team assistance. Validating small enhancement ideas with design and developer communities can be as easy as a Slack post and/or discussion in a critique.

On the other hand, large enhancements and new features can be much more costly. Proposals require multiple conversations to scope and prioritize feature details, design work iterates through one or two rounds with a design community, and code and documentation costs increase accordingly, taking weeks or months.

The relationship of frequency versus cost helpfully grounds conversations on how to model contribution workflows. In an ideal world, there’d be a continuous healthy flow of fixed defects and small enhancements from a wide community. The larger the feature gets, the more involved and longer the work is, and thus the more likely the central team is going to be involved to curate and guide the work.

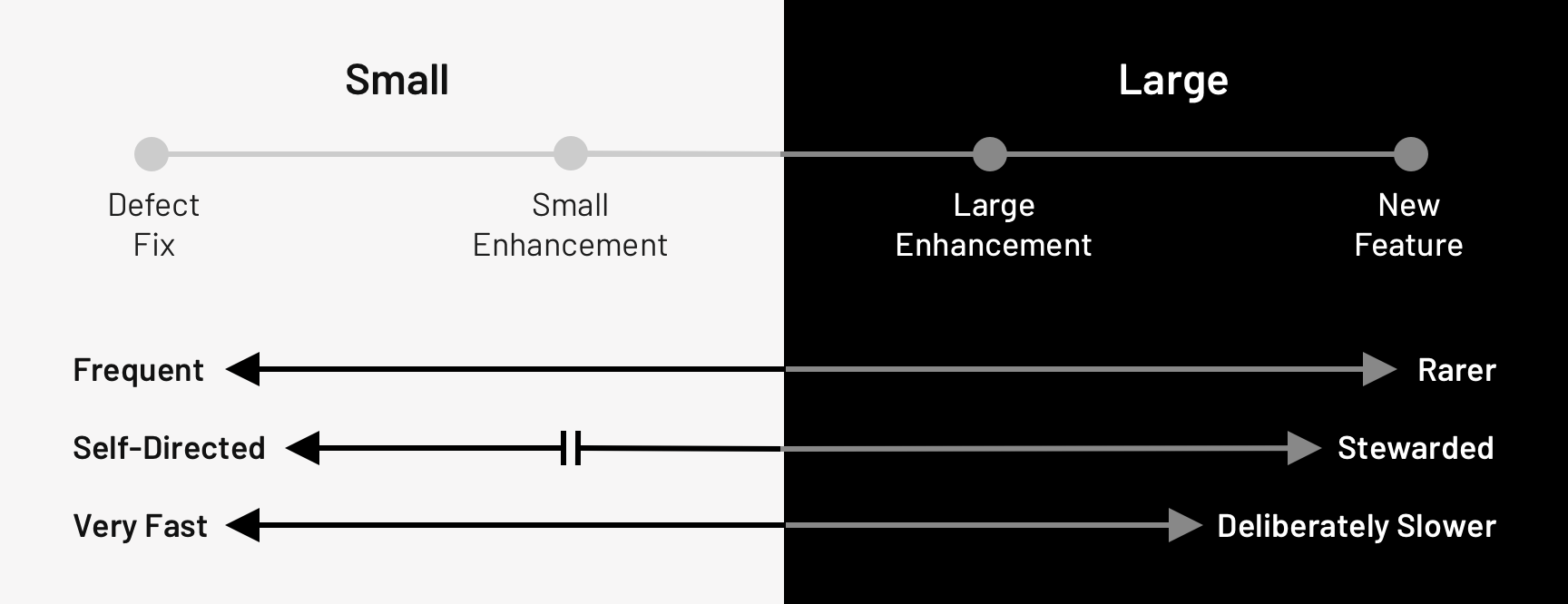

Some contributions are smaller, some larger. So what? Actually, the implications on contribution workflows work should be profound.

Teams can get really fixated on small contributions equating to the constant hum of code fix after code fix after code fix. Initially, this is helpful for focusing the team on optimizing the contributor’s job. For a small changes: How long does it take from identifying the opportunity through doing the contribution work (within system assets) to reintegrating that into their context (from system assets)?

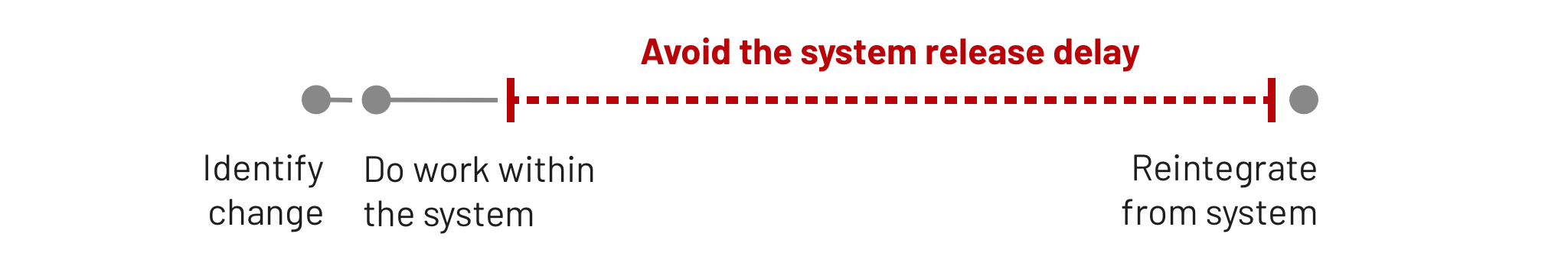

This optimization is critical, forcing system tools, documentation, and training to focus on a contributor speed and self-directed autonomy. The worst is when a contributor hustles to complete a change, but then a system doesn’t respond.

Instead, a system’s release process bundles code, design assets, documentation into some iteration (a two-week sprint? a month? a quarter?), and a contributor can’t use the fruit of their labor from the system for quite some time. Imagine their frustration! Instead, if they did the work, they are justified in expecting the system to enable them to use that work with all due haste!

Interestingly, it’s difficult for some design systems — particularly those where a core team releases by sprint — to invest in automation and relinquish control. Tooling, pipelines, and quality checks are costly, and teams can resist such automations despite a long term reward of contributions that outweighs the costs of change. This can creates an undercurrent of friction between a core team and contributing community that just doesn’t seem to go away.

However, small contributions aren’t just about quickly merging code into a source repository. Systems also need to quicken contributions across other outputs too. Often, I find myself advocating for specializing workflows for:

Such disparity makes clear the distinct tools, people, permissions, reviews, and other subtasks involved. These small changes need distinct workflows.

The last type — documentation changes — is quite a sore point for some programs. Design guidelines come nearly universally from designers and content strategists. Such staff are less likely to want to work in code and git. For some systems, such guidelines are ensconced in Markdown committed to a code repo, creating an insurmountable cost of entry. Other systems automate the publishing of Confluence wiki content to a polished documentation site, harkening a wild wild west of inconsistent, unreviewed content from the masses. Balance must be found.

Takeaway: Make small changes autonomous, frequent, and very fast from start to finish. As such, optimize each small change process that matters most. Start with code defects, and don’t ignore similar processes that benefit designers and other system participants.

Larger contributions are more costly, complicated, and involve many participants. A design system’s features are intended for wide consumption, and the work needed to normalize and agree on a solution is considerable.

Therefore, by necessity, a large contribution hews towards the rigorous process that a system team uses to get work done. In contrast to the diversity of workflows for small changes, a large change typically goes through all the steps: propose, design, code, documentation, release.

This makes larger contributions much, much harder, since:

Takeaway: Don’t delude yourself to think there’s a simple, basic set of a few steps for large contributions. Simplicity will need to give way to more complications in order to achieve the relevance, agreement, quality, and other criteria that system features require.

So, much to the regret of many system leads I talked to, large-scale soup-to-nuts contributions are hard. They are full of collaborative friction. And, as a result, don’t be surprised that they can be rare.

However, it’s what the community wants. And, as companies across our field begin exploring integrated design system tiers—web and mobile with a shared core, a core coupled with group-specific endeavors, and more — design systems will have to architect and automate how to do increasingly sophisticated contributions over time.

Takeaway: Increasing the quantity of large contributions will force many existing systems — delighting in their simple, contained, core processes — to grow and evolve. It’ll pain them. But they’ll get there.

EightShapes can energize your efforts to coach, workshop, assess or partner with you to design, code, document and manage a system.